Civic leaders and community members regularly put time and energy into caring and advocating for the environment. We call these acts of care stewardship. Beyond improving green and blue spaces, stewardship can also lead to other types of civic action. Local stewardship groups can strengthen social trust within a neighborhood. People who come together around the shared love of a garden or park steward not just that space, but also their relationships to one another—making them poised to organize around any number of issues affecting their community.

Who Takes Care of New York? was a public exhibition held at the Queens Museum 12-29 September 2019 that highlighted the stories, geographies, and impacts of diverse civic stewards across New York City through art, maps, and storytelling. This transdisciplinary show was organized by the NYC Urban Field Station; Pratt Institute’s Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative; and independent curator Christina Freeman.

It drew upon the USDA Forest Service’s Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project (STEW-MAP), which is a dataset of thousands of civic stewardship groups’ organizational capacity, geographic territories, and social networks. STEW-MAP has been implemented in approximately a dozen global locations; it was piloted first in New York City in 2007 and then updated in 2017, which was the source of the data that were used in this exhibit.

The show featured artists whose work aligns with the themes of community-based stewardship, civic engagement, and social infrastructure: Magali Duzant, Matthew Jensen, Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow, and Julia Oldham. Through photography, drawing, book arts, and performance, these artists reflected upon, amplified, and interpreted the work of stewards and the landscapes and neighborhoods with which they work.

This essay excerpts content taken from exhibition wall text, data visualizations, and artists’ work—interspersed with comments from the curator. The video below is a virtual tour of the exhibition.

What is stewardship?

When you take care of a place you love, you are engaging in stewardship. Whether you pick up trash that you see in your park, band together with a few neighbors to tend to the trees in front of your building, or teach the next generation about the importance of biodiversity, you are joining a network of care that keeps cities like New York green and flourishing. Caring for the environment happens at different scales, and there are roles for all sectors: public, private, and civic. Most often, civic environmental stewardship happens in groups—from a couple of friends, to small informal associations, to citywide or even international nonprofits. But sometimes the important work of these civic groups can go unrecognized. This exhibition aims to make these groups more visible.

The first artist perspective that I will highlight here is Matthew Jensen. Training his eye on the street tree, he reveals the incredible diversity and resilience of this form of nearby nature that is for many New Yorkers (including me) and for many urban dwellers around the world—their first entry point into stewardship action. As a qualitative social scientist interested in place meanings, I found many resonances with Matthew’s multi-modal approach to research (photo documentation, interview, mapping, archives). His process of walking and observing the landscape has taught me a great deal about the porous and blurry line between art and science. He is not only an observer, however, he is also a participant, as he trains himself in the practices and tactics of his subjects, such as becoming a Citizen Pruner to better engage in the care of trees.

Matthew Jensen

This photographic series celebrates the myriad of ways city residents care for street trees and the spaces surrounding them. Jensen is especially taken with what he refers to as New York’s amazing trees— distinctive for their impressive size, ability to thrive in unexpected locations and defy such obstacles as, extreme damage or abnormal habitat. Jensen’s project recognizes a diversity of practices—from homemade tree guards and creative support systems, to ornate gardens. Through the process of documenting, the artist also participates in his own form of tree stewardship.

Matthew Jensen is a Bronx-based interdisciplinary artist whose rigorous explorations of landscape combine walking, collecting, photography, mapping and extensive research. During his 2017/2018 artist residency at the NYC Urban Field Station he developed his current project The Forest Between: Street Trees and Stewardship in New York City.

Stewardship comes in all shapes and sizes

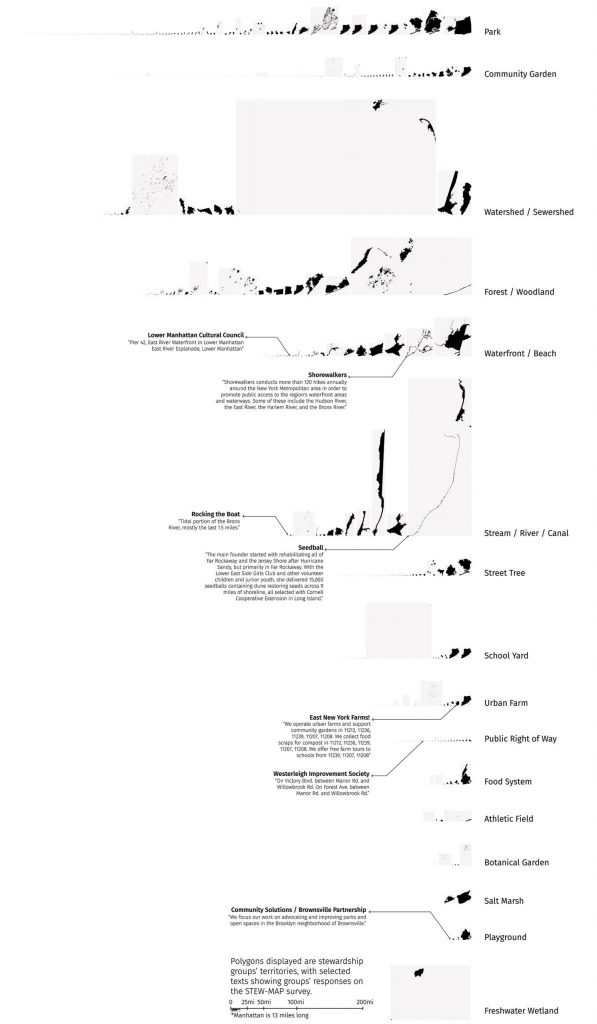

Stewardship territory reflects each group’s claim on space; it is their basis of power and their landscape of care and concern. Territory ranges in scale from a single tree, to a watershed, to an entire region. It varies in shape and can include rectangular lots, linear strips, curving shorelines, and blocky political districts. For some stewards, such as community gardeners, territory is the specific site where physical land management occurs. Other groups focus on advocacy across wider spatial scales, such as environmental justice groups running neighborhood air quality or green job campaigns. Finally, some groups focus on transformation of waste, food, or energy systems, and therefore have multiple sites across the city.

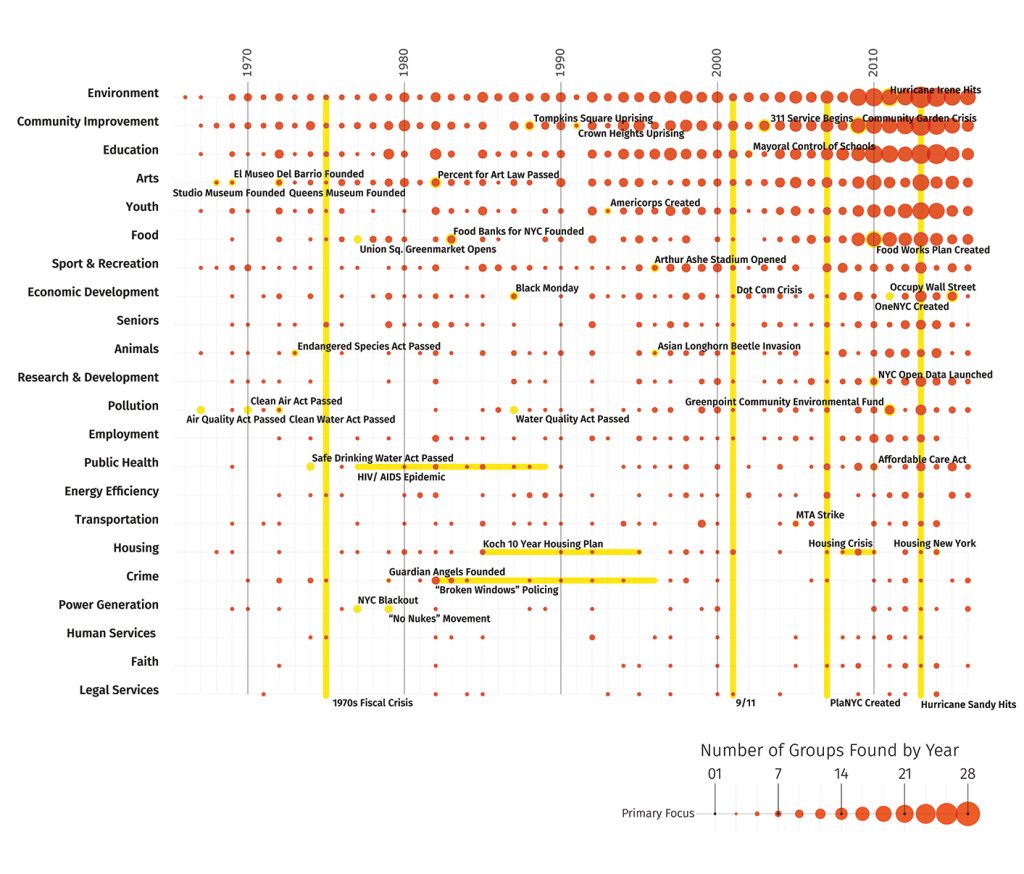

Stewards respond to disturbance

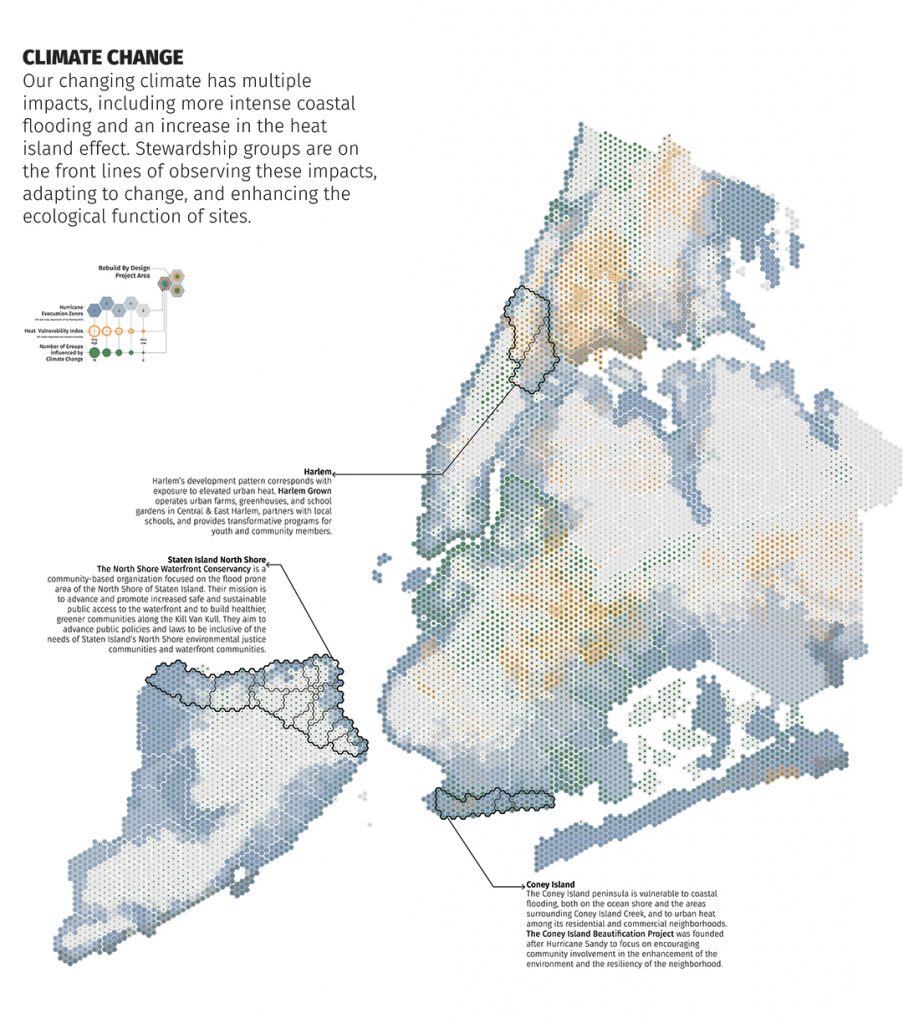

Stewardship is one of the ways that communities respond to social-ecological disturbances and stressors, including both disinvestment and gentrification, as well as climate change and its attendant weather extremes. This pattern has repeated over time here in New York City, with stewardship groups forming in response to the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, September 11th, and Hurricane Sandy. The act of caring for local places can transform not only the physical environment, but also our relationships to those places, and, perhaps most importantly, our relationship to each other. It is this shared sense of trust and reciprocity that serves as a building block for the radical changes that are required to steer our cities toward a more just and sustainable future.

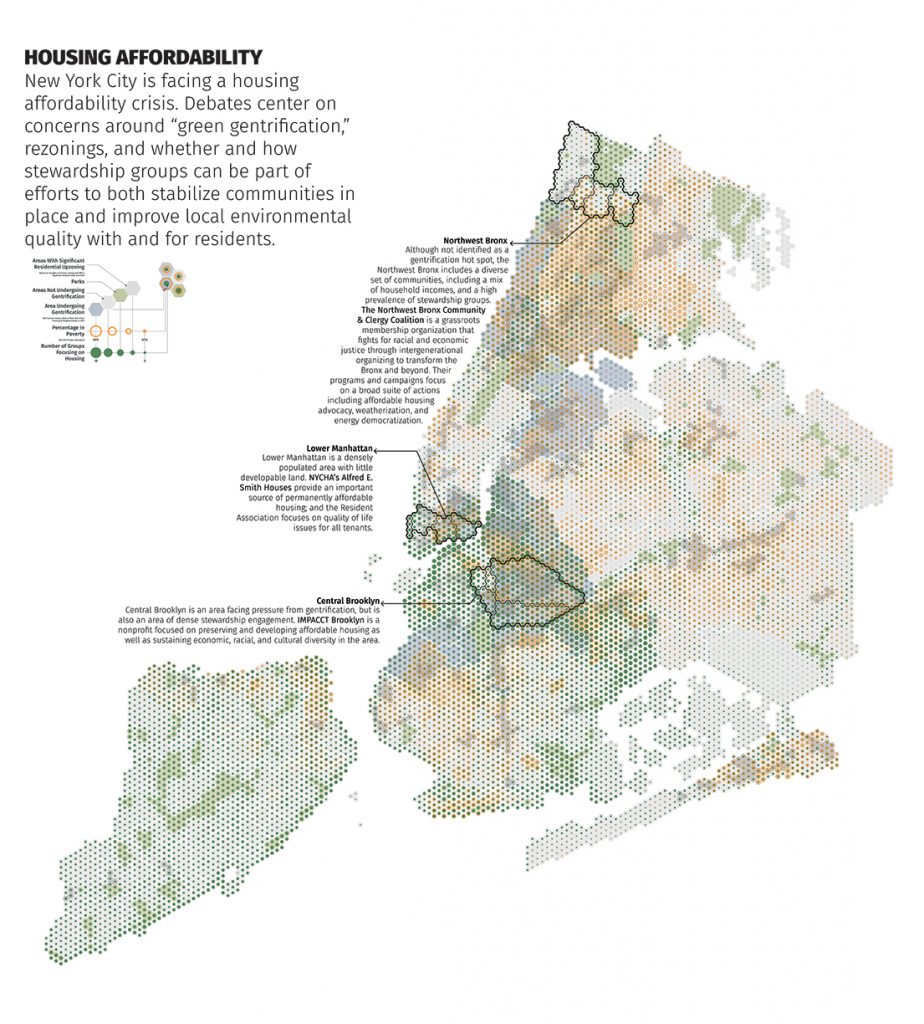

New York City is facing a housing affordability crisis. Debates center on concerns around “green gentrification,” rezonings, and whether and how stewardship groups can be part of efforts to both stabilize communities in place and improve local environmental quality with and for residents.

Julia Oldham’s artistic work helps us think through stewardship and connections to nature in the era of climate change. Across Julia’s body of work, she imagines both dystopian and more hopeful renderings of our future. She also points out spaces that are often neglected by humans—where human/nature/animal relations have undergone a radical reworking—as with her video “Fallout Dogs” about the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

I was excited to see what sorts of spaces or futures Julia might envision for New York City. At the same time, these futures are rooted very much in the embodied experience of being there—Julia is an intrepid explorer of wildernesses both urban and rural and never travels without her wellies. It also reflects the importance of talk. She interviewed dozens of government workers and volunteer stewards to find both their favorite wild places and to understand their hopes for the future of those places. In particular, Beaver Village reflects Julia’s truly inter-species affection for living things, and playfully imagines a different way in which we might cohabit with non-human others.

Julia Oldham

Oldham’s series presents an amalgamated vision of New York City’s future, inspired by conversations with those most intimately connected to its wilderness. During her New York City Urban Field Station residency, the artist used the STEW-MAP database, to connect with nearly 40 stewards of the city’s natural areas. Asking scientists, park rangers, gardeners, beekeepers, educators and volunteers to share their views—especially in regard to nature and climate change—Oldham collected projections ranging from the utopian to the less optimistic.

The visual narratives here are a combination of Oldham’s own methodical documentation to create a unique 360-degree photograph, followed by a process of digital collaging with satellite images, drawings, and found photographs. Julia Oldham’s work expresses moments of hope in a world on the edge of environmental collapse. Working in a range of media including video, animation and photography, she explores potential in places where human civilization and nature have collided uneasily.

Stewards are agents of change

The power of civic environmental stewardship groups comes from their ability to create lasting change through direct action, management, education, and advocacy. Beyond environmental benefits, civic environmental stewardship groups provide opportunities for people to get to know one another and beautify their community in the process. These actions create a sense of social connection and a feeling of ownership and place attachment. Stewardship groups work on everything from restoring New York City’s oyster population, to protecting natural areas from development, to helping women get outside to exercise and form empowering friendships and civic ties. Taken together, these efforts can collectively transform our environment and communities.

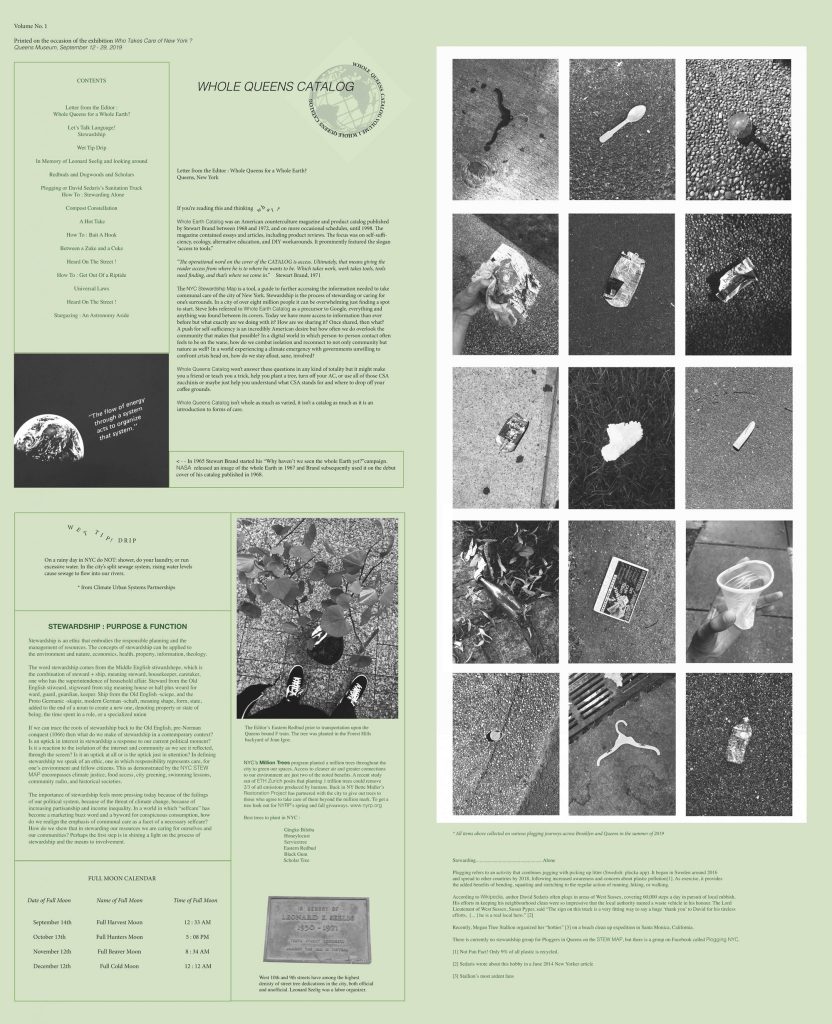

How can we understand both the collective impact and individual experiences of these thousands of stewards? Magali Duzant’s work takes a deeper dive into the knowledge, practices, and actions of Queens, NY-based stewards, revealing that each of these dots on a map is comprised of important (and even sometimes humorous!) lifeways and histories. In order to uncover these stories, she queried the STEW-MAP database, scoured the internet, and talked with stewards. A self-professed outsider to the world of environmentalism, Magali shared that she found surprising resonances between the network of stewards and her existing world of artists and arts organizations. Everyone was just a few links from each other, and was happy to pass on another recommendation, a site to visit, and event to participate in. Magali navigated that network of relationships to create a new publication that could serve as a sort of “starter kit” for an interested novice to get involved in stewardship work (and play) in Queens and beyond.

Magali Duzant

Whole Queens Catalog is a free (limited run) publication commissioned for Who Takes Care of New York? Magali Duzant’s new commission, Whole Queens Catalog, takes inspiration from Stewart Brand’s 1960’s American counterculture magazine and product catalog (Whole Earth Catalog). Duzant has gathered anecdotes, recipes, disaster survival techniques, and other wisdom from stewardship groups throughout Queens that she identified from the STEW-MAP database and additional research.

Magali Duzant is an interdisciplinary artist based in New York. Her work spans photography, books, installation, and text. In collaborative and participatory approaches to projects, she couples research-based practices with a poetic knack for capturing where public and private experiences converge.

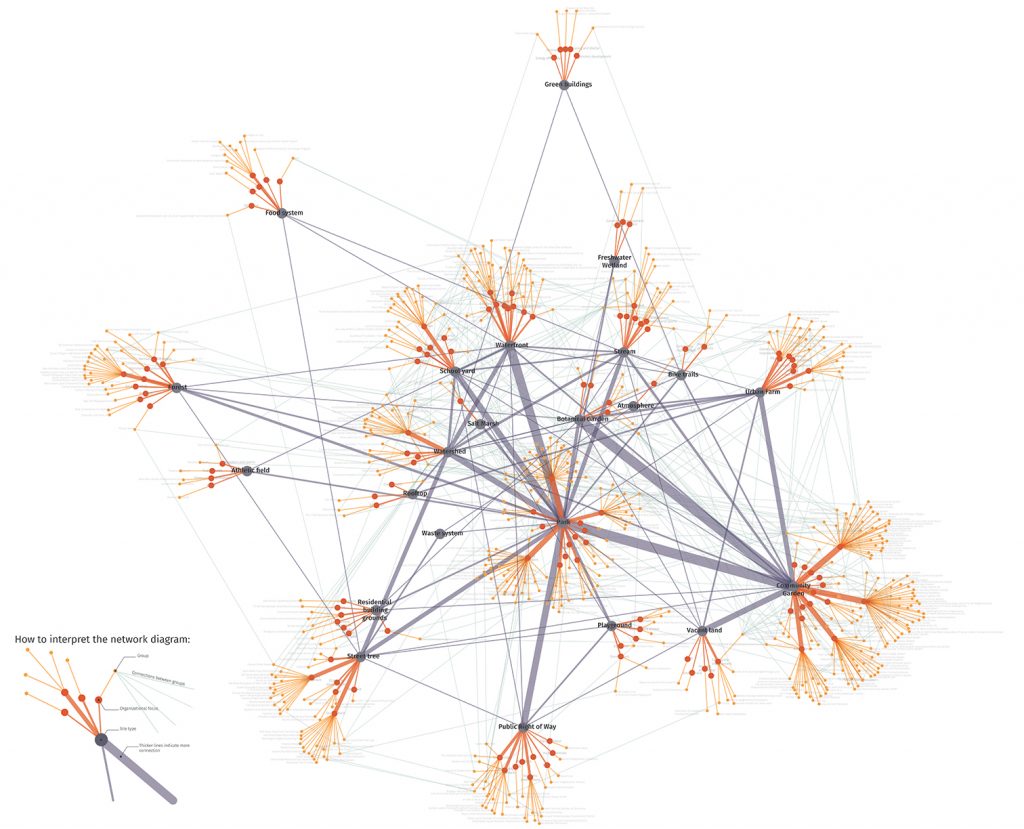

Stewards work together

Civic stewardship groups collaborate across a broad constellation of stakeholders. Whether they need more volunteers for an event they are holding, a bag of compost for their garden, or information about how to build their own tree guards, the larger stewardship network provides. STEW-MAP asked groups who they work with in order to visualize these vital connections of ideas, materials, labor, and capital. Over time, these relationships shape governance across civic, public, and private sectors, and influence the policy agenda and the form of the city.

NYC Parks, the largest land manager in the city, is also the most connected broker in the entire stewardship network. Partnerships for Parks is the central broker in New York City’s civic stewardship system. Working with hundreds of “Friends of Parks” groups across the city, they were removed from this visualization in order to see other connections between groups:

Visualizing the power of sometimes subtle forces is not easy. How do we show the strength of a network? Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow’s work uses a patchwork dress, a picnic, a participatory performance—each of these forms demonstrate the way in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Lyn-Kee-Chow has created a series of picnic performances staged in various locations of the public realm of New York City—including streets, parks, and museums. While the artist herself anchors and orchestrates these performances, she engages others both as co-performers and as participants. For this piece, Lyn-Kee-Chow invited stewardship groups focusing on food justice work to share their wisdom, their harvests, and their relationships in a conversation and celebration on the outstretched dress-as-gathering-space. Throughout the rest of the show, a similar dress hung as a symbol of this gathering.

Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow

Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow’s participatory performance on September 15, 2019 honored stewardship groups in the five boroughs whose work centers around food justice issues. Lyn-Kee-Chow was joined by representatives from Edible Schoolyard NYC, Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center, Smiling Hogshead Ranch, and Sunnyside CSA, groups she learned about through the STEW-MAP database. These organizations serving The Bronx, Brooklyn, Harlem, and Queens were highlighted for their projects organized by and supporting New York City’s communities of color and immigrant populations.

Since 2010, Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow has created a series of picnic performances that set up space for the public to have conversations. Inspired by the kitchen tablecloths of her grandmother, she sews together vinyl tablecloths from bargain stores, creating elaborate dresses that double as picnic blankets. Embracing her mixed Chinese and Jamaican heritage, her projects reflect on multiculturalism, food migration and the colonial food trade. Hailing from a lineage of farmers on both maternal and paternal sides of her family, food justice has a particularly personal connection for the artist.

Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow is a 1.5 generation Jamaican-American interdisciplinary artist living and working in Queens, NY. Her work often explores performance and installation art, drawing from the nostalgia of her homeland, Caribbean folklore, fantasy, globalism, spirituality, and migration.

Stewardship timeline

Stewardship groups not only exist, they persist. They have evolved along with the social, political, economic, and environmental histories of our city.

This animation shows the emergence of stewardship groups by year founded, including the proliferation of groups after the 1970s.

The timeline calls out selected key moments and turning points in New York City’s stewardship history.

Stewards in their own words

Quotes were collected from interviews with a subset of stewardship groups. USDA Forest Service researchers asked stewards to share their definition of stewardship, stories of ways in which they helped to take care of the environment, and their vision for the future of stewardship work in NYC.

Finally, we have been gathering personal accounts of people’s stewardship stories from all over the world. These narratives range from cherished memories, to everyday occurrences, to sparks that started social movements. To add your own story to the map, go here!

In the future, I could imagine a whole series of exhibitions—Who Takes Care of Paris? Who Takes Care of Cairo? Who Takes Care of Delhi?—featuring the faces and actions of stewards in each of these places combined with artistic perspectives on that work. Not only global cities across the world, but also mid-size cities, smaller towns, and rural areas have their own stewardship stories to tell. Perhaps we can begin to see more clearly the ties of care and connection that bind us all.

Lindsay Campbell

New York

Acknowledgments: Who Takes Care of New York? was organized by the NYC Urban Field Station, a partnership between USDA Forest Service researchers (Lindsay Campbell; Michelle Johnson; Laura Landau; Erika Svendsen), NYC Parks (Caitlin Boas), and the Natural Areas Conservancy, with a mission to improve quality of life in urban areas by conducting, supporting, and communicating research about social-ecological systems and natural resource management; Pratt Institute’s Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative, SAVI (Jessie Braden; Can Sucuoğlu; Case Wyse; Josephina Matteson; Zachary Walker; Lidia Henderson), a multi-disciplinary mapping research lab and service center within Pratt Institute that focuses on using geospatial analysis and data visualization to understand NYC communities; and Independent Curator, Christina Freeman. Thank you to the thousands of stewards across this city whose work we aimed to amplify in this exhibition.