Introduction

As human beings who inhabit bodies made mostly of water, connecting to water as an element means connecting to a large part of who we are. Yet more than this, the artists in this roundtable teach us that if we pay close attention, water can help us connect in profound and useful ways to the environments around us.

Artists who work closely with water seem to take upon themselves a duty, to help us remember, imagine, and even embody the importance of water to life on this planet, and in our cities. They remind us that rivers run through our cities, but also through our bodies. In connecting the water within us and the water that makes up the world around us, they offer opportunities for the kinds of deepened relationships with the Earth that our society can benefit greatly from. Here, water becomes both teacher, and a sort of guide for us to imagine how we might build cities with respect for this precious element.

In cities, water flows through human infrastructures, from drinkable water systems and agricultural fields, to sewerage systems, it travels through pipes, channels, ravines, aquifers, and treatment plants. Yet water continues to follow its ancient patterns too, ever present as the cohabiting sea, lake, wetland or river, streams, taking form in the weather; the monsoons, the snow storms, and the periods of drought, where withering landscapes, and their co-inhabitants, respond to its sudden absence.

Human settlements are responding to water-related issues constantly. Streams and rivers are covered by urban expansion in one area; elsewhere others are unburied and restored. In many parts of the world water pollution is egregious, with two billion humans lacking access to clean water, and countless other beings in nature suffering even worse fates; elsewhere laws to regulate pollution and waste are mitigating or reversing these pollution and access issues. As sea levels rise and climate change affects our cities more broadly in unpredictable ways; in parallel we adapt and protect, creating ecological parks to form living buffers and promoting vibrant water-protecting ecosystems.

On an even more fundamental level, changes to social attitudes towards the precious resource of water – often attained through the collaboration of arts and science – are driving efforts to create more long-term sustainable ways of living and being with this Earth.

For this, our second roundtable, we invite eleven artists to present their conversation with water in cities. Coming from seven different countries—Czech Republic, France, Mexico, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, and the United States—these artists inspire our own experiences with water in cities. They engage with water in the shape of fog, rain, ice, restored wetlands, urban rivers and creeks, city fountains, and reclaimed urban spaces. To them, water is an inclusive moving matter that when listened to, can serve as a conduit to larger understandings.

Water is vital, spiritual, and restorative. It is a common that connects us all, to each other, and to our biosphere. The conversations here take various forms, from the performative to the media-based, from poems to sculptures to design, and from community and civic engagement, to methods of collaborative caring for water and for each other. We are pleased to have you discover these conversations with us, and invite you to further enrich them by responding to the work and perspectives together.

Carmen Bouyer and Patrick M. Lydon

Panel Co-Chairs

Banner image: “Ice Receding/Books Reseeding” projects. “Cleo reading TOME II.” 300-pound ephemeral ice sculpture embedded with native riparian seeds. Photo: Basia Irland

Antonio José García Cano

Murcia

Learning from the water

I live in Rincón de Beniscornia (Murcia), a small village in South East Spain. It is in a traditional irrigation area called Huerta de Murcia located in the floodplains of the Segura River, very close to the city. In this place, water has been essential for the economy, culture and landscape. Over centuries, the river has flooded the area and people made a living from varied agricultural activities.

Art can lead us to reflect on our relationship to place: promote place attachment, point out the ecological and cultural values, and generate dialogue and imagination about the future.

However, today the place has changed deeply: urban developments have been built on top of fertile soils, the river has been channelized and engineered, and parts of the irrigation channels have been funneled into pipes under roads.

Not many people still cultivate the land, and water has become scarce.

The ecological values of the ecosystem have been degraded. In addition, climate change is bringing more challenges, among them higher temperatures, droughts, and floods.

From my perspective, art can promote reflection about our relationship with place. These are some projects where I try to promote attachment to the place, point out the ecological and cultural values that still remain, and to generate dialogue and imagination about the future of those places.

Azarbón (2009, Rincón de Beniscornia, Murcia, Spain)

Azarbe or Azarbón is the channel that collects the water that has not been used to irrigate the lands and brings it back to the river. When I was a child I used to play there. My grandparents fished and played there, drank that water and used it to cook.

Nowadays, you cannot see water very often and it is not drinkable.

I did an artistic intervention in this place using reeds (Arundo Donax) which is an invasive plant but very used historically here. The goal of this piece was to keep the memory of flowing water alive in that channel. In the short film Azarbón you can see how the artwork was created and also learn from the memories of José Cano Cano and Antonia Cano Cano about this place.

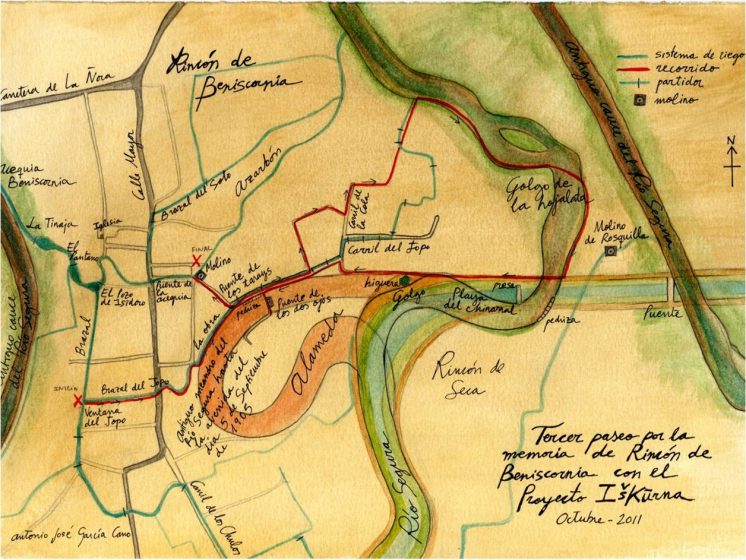

Iskurna Project (2011-2014, Rincón de Beniscornia)

In Rincón de Beniscornia, I began a process of learning about the place from the elders, from old photos and ancient maps and documents. I understood how the river had been a living organism moving in the floodplain for centuries until we constrained it by levees and how important the smart irrigation system is. I walked with people who live there and outsiders to share my knowledge, to keep on learning from them, and to generate connections and learning networks.

I drew maps of the place where you can see features that do not exist any longer like the last river or acequias. They also include the traditional names of places.

We filmed eight videos of a farmer (Joaquín Martínez Ortín) doing traditional agricultural tasks, such as preparing the soil, planting potatoes, or watering the plants. They are part of the series of videos called “The cycles of the orchard”.

After these two projects, I understood this as an ideal place to develop a strategy of adaptation and mitigation of climate change. Therefore, I published an article in Ecosistemas science magazine about how we can promote connectivity between the current river, the last meanders of the river and the irrigation channels to embrace different effects of climate change. This system could surround the city, Murcia, and generate a green corridor which regulates temperature, provide shelter, generates oxygen and sink carbon dioxide. In addition, if we eliminate some of the levees of the river and generate natural areas to flood and we also open partially the old meanders, we could embrace floods and promote life at the same time.

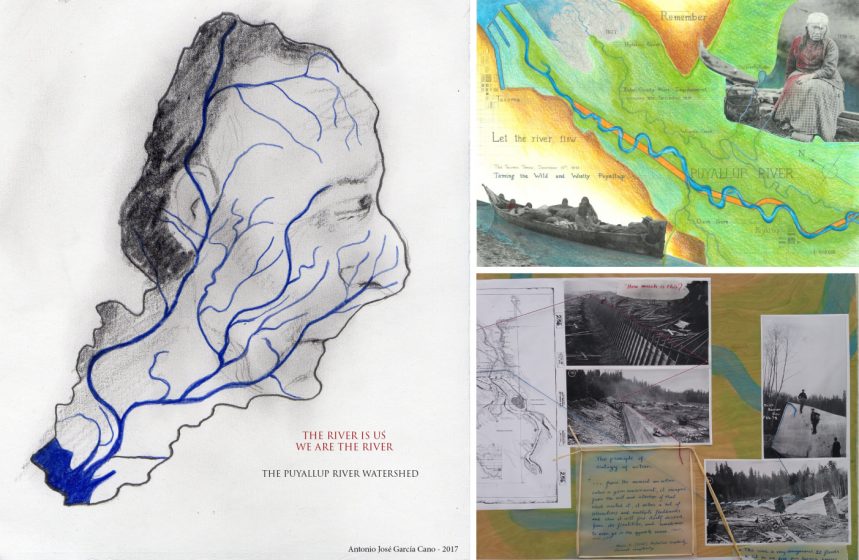

Puyallup Project (2016-2017, Tacoma, WA, USA)

Last year, I was an artist and postdoctoral research fellow at University of Washington-Tacoma supported by a Fulbright Scholarship. Below is one of the arts-based projects developed during this time, a process of connecting with the community and scientists, collecting memories, photos, maps and other memories about the Puyallup River in order to learn about how the community had related to the river.

I developed the exhibition Let the River Draw Again with a mural about the river, a video, collages, some drawings, old photos and maps of the channelization works and questions about how we relate with rivers in urban areas. I learned that Puyallup People had lived for thousands of years sustainably and that in the beginning of the twentieth century the river was channelized to control it.

However, recently, there is good news that Pierce County (WA) is developing a project to reconnect the river with the floodplains.

For me, this is a sign of how we can change the paradigm of controlling rivers to a paradigm of living with them. We need to design plans of coexistence instead of plans of defense from rivers and from nature in general.

How can we learn from the places and their ecological dynamics to evolve with them promoting life and resilience?

How can we learn from those who have lived in a place over centuries and from their culture?

From my perspective, art can facilitate the conversation and raise questions about our relationship with the place.

I am now drawing some of the possible futures for the river in the place where I live in order to share them and promote dialogue and hope about how our relationship with the place could be.

Claudia Luna Fuentes

Saltillo

Water: the blood of the world. Creative processes around.

I grew up in a desert, where the sun calcinates the tender buds that have no protection from trees or roofs, where the water slowly evaporates at 45 degrees centigrade. Here there are urban communities that see the water of their rivers contaminated by industries, and rural communities that defend water from the dispossession of cities or the presence of toxic waste deposits. And also, in counterpoint, I grew up with a family that was looking for water to submerge their bodies. That was my childhood: trips to the heart of the desert to swim in pools of water of the valley of Cuatrociénegas and see silhouettes of fish, turtles and grasses, salts and their marks.

Some poems give an account of this relationship, and also some photographs of oxidized metals by the action of water, which account for the work of workers in the desert.

The presence in the community of actions and elements originated from art has provoked a reflection beyond art.

Forest, water, and community

I started writing about forest and water, from a training that made me cross 28 kilometers of the Sierra Madre Oriental. There began the spell, observing the darkness I entered, and then, the dawn with the frozen mantle of fog refreshing my face. Spider webs full of dew were added like diamonds because of the sun that was beginning to appear, also the needles of the bright pines with the soft humidity deposited, the perfumes of the flowers and the earth, the gift of the landscape. I wrote a text in a local newspaper. This writing resonated with an inhabitant of Saltillo, Alejandro Arizpe, who contacted me to write poems and take photographs of this part of the Sierra Madre, called Sierra de Zapalinamé. Thus, in 2009 we published Diario de Montaña. Without proposing to us, we set up a movement based on art, which makes visible the protected area of this mountain range, whose wells offer Saltillo more than 60% of the water. This water motivated the foundation of the city and owes its name: Saltillo, Salto de agua: jump of water.

We call this initiative Yo Soy Zapalinamé and it was consolidated, when observing a construction company invading lands next to the protected area. The work includes publication of poems, a conservation guide to the mountains, reading poems, concerts in nature itself and a musical festival in the protected area.

We also convened through social networks and media, to form a collective citizen that saw the light in 2014 and performs interventions of urban art called environmental communications, as they include common and scientific names of species, as well as conservation phrases.

We are currently in the process of proposing a legal figure that allows citizens to acquire, with small contributions, a percentage of the protected area and avoid reducing the number of hectares.

Personal work

The creative process led me to generate a different support to the book for the poems. In 2014, invited by the Contemporary Art Gallery MACO, Quintana Roo, I wrote chronicles about the biodiversity of the jungle and mangroves; They were made during an expedition with the artists Irma Palacios, Gabriel Macotela, Alberto Castro Leñero, José Castro Leñero, Patricia Soriano, Teresa Zimbrón and Mauricio Colin.

Water became important, until it became a collection of poems. With the support of a PECDA Coahuila 2014 scholarship, I wrote a book of poems initially called “What saves a legion of fog”, inspired by the water and biodiversity of the Sierra de Zapalinamé.

For the reading of this book of poems, I invited the sound artist Mike Campos. We did interventions in book fairs in Saltillo and Monclova, where water is a controversial issue. For these readings we collect sounds of water, stones, grass and wind in the protected area, and we include water sounds in real time.

And as part of the same effort, in 2015 I gave a workshop for young people based in the protected natural area; the participants generated poems and a piece with sound records of the site.

Video: Water: Our Skin

POEM: “Fog” (excerpt). Read the entire poem here.

It is said that fog is a very low cloud, which is made of tiny drops of water that never stop falling. It is said that fog in order to be fog, must be so thick that it obstructs the vision; that if you look ahead, it is possible to see no more than one kilometer. All that is true, but we say that Fog is the will of Water, the Water that walks standing behind a veil. We say the Fog is our Lady and it is sacred.

— Poem by Claudia Luna Fuentes, from “2046, year of our lady The Fog. (Versión Gerardo Mendoza Garza)”

Recently, in collaboration with videographer Reginaldo Chapa, I produced a short film that has as a script part of the poetry collection “What saves a legion of fog”, now under the title 2046: Year of Our Lady the Fog. Mike Campos generated the soundtrack; is also conceptualizing sound pieces from this book of poems.

Currently I continue with interventions in rusty cans found in expeditions to the desert, I add images of flora and fauna of the desert, and also words.

As part of this poetics, from recycled glass and ceramics I generate containers and elements that store water or reflect on it. I create visual poems made with earth tones obtained from the site, liquid gold leaf, candelilla wax and filaments of ixtle extracted from the lechuguilla -a plant present in the interconnection of desert and forest-. I use water from a spring in the protected area, mixed with my blood, in reference to the struggles and conflicts over water, and also, to allude to the foundation of life: water.

This is my conversation with water, which has allowed the presence in the community of actions and elements originated from art, to provoke a reflection beyond art. I look for the representation of reality, from step to action in reality itself.

Katrine Claasens

Montreal

Wild Water

In Cape Town, we thought we had domesticated water, but we had only tamed it, and taming can come undone.

In the city the water goes neatly, invisibly through underground pipes. It performs pretty tricks obediently in the fountains and it submits its rivers to discreet concrete channels that run unnoticed by highways, silently whisking the water out to the sea. For many in the city, water comes out of a faucet, clean and guaranteed.

We had been lulled into hypnotic tap-water love. We filled our lives with the tamed water: swimming pools, fish ponds, saturated lush lawns.

In the Southern Suburbs, we had been lulled into hypnotic tap-water love. We filled our lives with the tamed water: swimming pools, fish ponds, saturated lush lawns. Water provided the very soundtrack of our lives—the soft white noise of sprinklers and faraway lawn-mowers, the shrieks of children in the swimming pools.

Swimming pools are a perfect example of how tamed water can quickly become wild. They need to be constantly tended. Scooped daily of leaves, refreshed with chemicals, topped-up with the hose. For all intents, this is dead water, but water that must be worked at to be kept dead. Without attention it rebels with algae blooms—becoming green, soupy, alive—a new ecosystem where little things can begin to live.

But there can be wilder water still: in between the blue swimming pools there is secret water, water that comes up like weeds, and is often as unloved. There are blocked drainpipes that hold old water as baths for the birds and breeding ponds for mosquitoes. The murmuring complaints of streams diverted underground in the stormwater drains near the mountain. The occasional flooding of the Liesbeek River, asserting its ancient territory and depth. The excitement of a burst pipe in the street. Sometimes water long gone leaves a stain; a built-over pond where small frogs come back each year, looking for lost water.

And then there is rain, the traveller, the wildest water of all, to whom all places are alike. It is through rain, more precisely the lack of rain, that we came to know water as wild again.

There has been a drought in the Cape, one that has silenced the sprinklers and made the lawns dusty and brown. The city told us ‘Day Zero’ would come – the day when water would not come out the taps. The drought has acquainted us suburbanites with the weight of water as we carry buckets from the shower to water the garden. For the first time in over a hundred years, people queue to collect water from the mountain streams. Water is no longer guaranteed and anonymous, but something that comes from somewhere, something that is precarious and precious. It brought the outside into the city – faraway dams came into focus and we learned their names, and then what they looked like at their bottoms.

The drought awakened something ancient, something that scratches in the back of the mind about there not being enough. It also harkens to a future time when the nipping sea waters might rise to take the city again. We walk unwillingly into water wilderness; we have stepped outside.

Robin Lasser

Oakland

Operation Ice Ships: Love Letters in the Time of Climate Change The ice ships are clear and black ice cubes, in the shape of the Titanic, melt in front of the camera, to a soundtrack of love letters sourced from the community.Melting glaciers may be the most visible barometers of climate change. The fatal collision of the Titanic comes to mind, when thinking of the glacier as an icon. Somehow love makes its way into both scenarios. To love is to connect, to protect and ultimately to care. Or do we destroy what we love? This film references the science of melting ice, rising sea levels, and the trauma of love in the time of climate change.

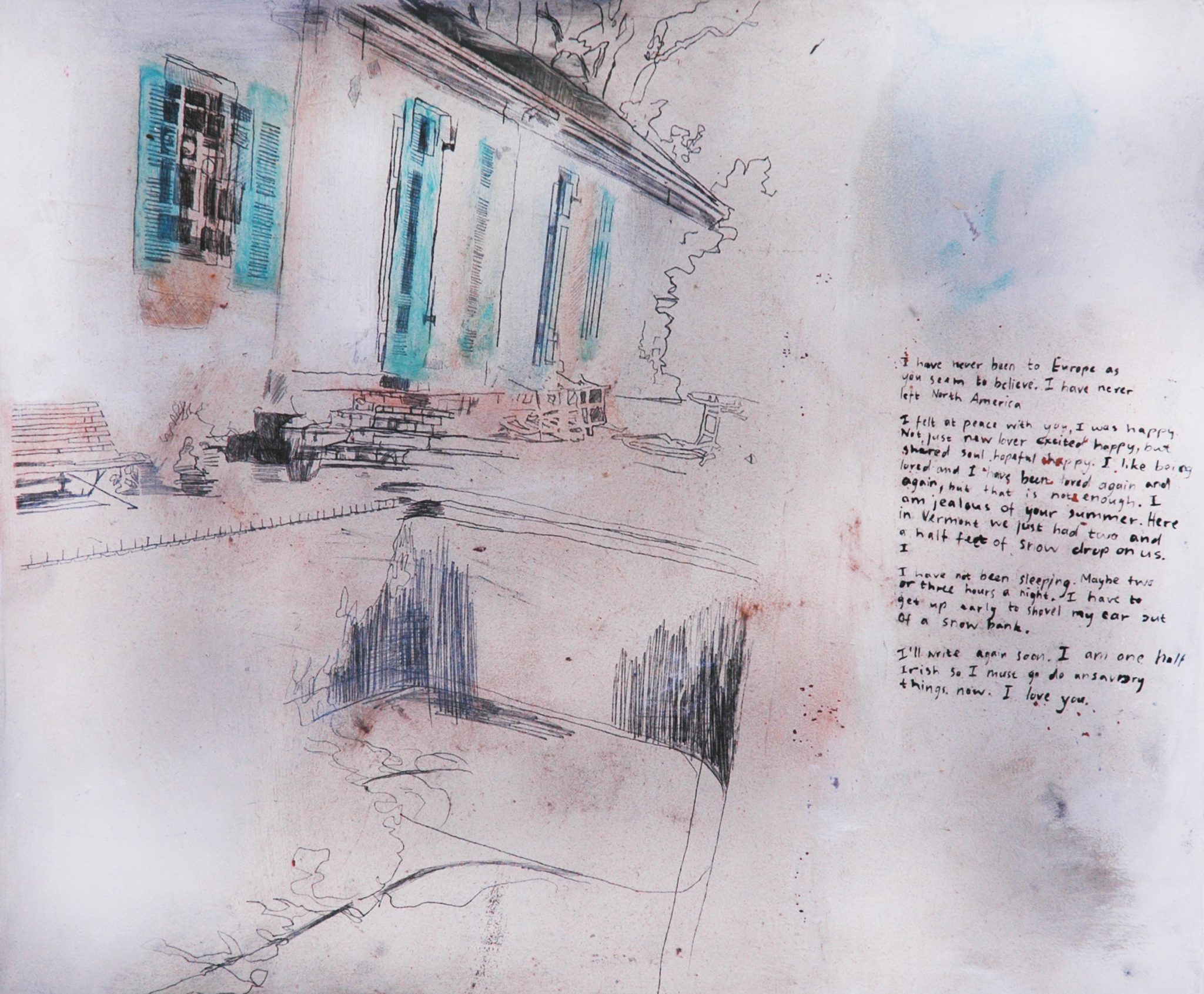

Video: Operation Ice Ships: Love Letters in the Time of Climate Change, 16-minute two channel mapped video installation, 2017

Technical notes and community engagement

The ice ships are clear and black ice cubes, in the shape of the Titanic. They melt in front of the camera, the contents of the melt down literally create the landscapes/environments they are filmed in. The love letters in the sound track are sourced from the community.

In the film, the love letters are gifted by San Jose State University students. I head the Photography Department and often engage my students in community-based pieces that highlight environmental and social justice issues. I do this as a form of activism, a way to work metaphorically and at the same time activate the communities I live and work within.

This climate justice project references water in relationship to the city of San Jose. Our students have emigrated from around the globe, the sound track reverberates with love stories spoken in multiple languages. The local meets global with our shared global commons, our oceans and seas.

The project crossed the nation and premiered at Pensacola University in Florida. The University is in close proximity to the Gulf of Mexico where the Deepwater Horizon oil spill occurred. The gulf oil spill is recognized as the worst oil spill in U.S. history. In Florida the film was mapped and projected onto the gallery exterior façade. The right-hand side of the façade reminiscent of the shape of a typical water tower. Pensacola students drew love letters onto the face of floating Japanese lanterns. The students activated the floating lanterns and read their love letters in open-mic format for the duration of the event. The project continues to travel, the most recent iteration taking place at the Albrecht Kemper Museum of Art in a show curated by Marguerite Perret tilted: “Memory of Water: Defining a Sense of Place in the Hydrosphere.”

Bonnie Ora Sherk

San Francisco

Islais Creek Watershed

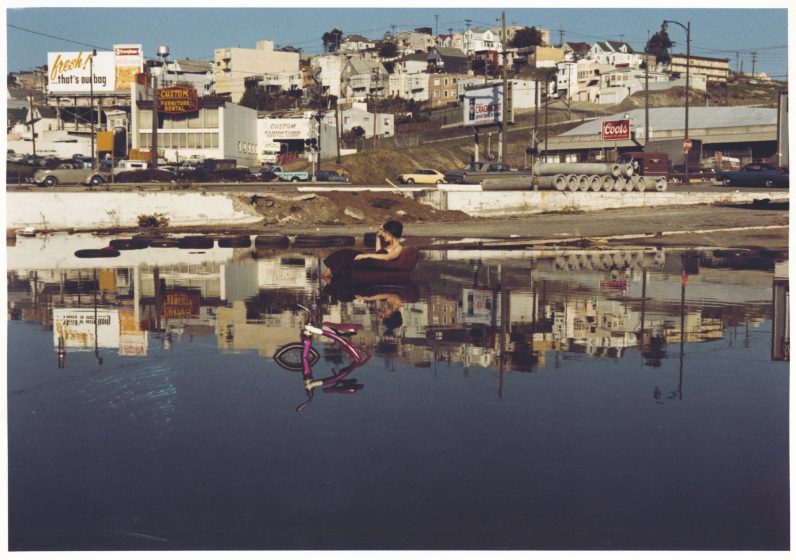

The Islais Creek Watershed is the largest Watershed in San Francisco, California, and one that has played a significant role in my life and art for decades beginning in 1970, when I found an area where garbage and water had collected because of the building of a major freeway interchange. This place soon became the site for Sitting Still l, a temporary performance installation in which I became the human figure in an evening gown sitting in this environment facing the audience of people moving slowly in their cars.

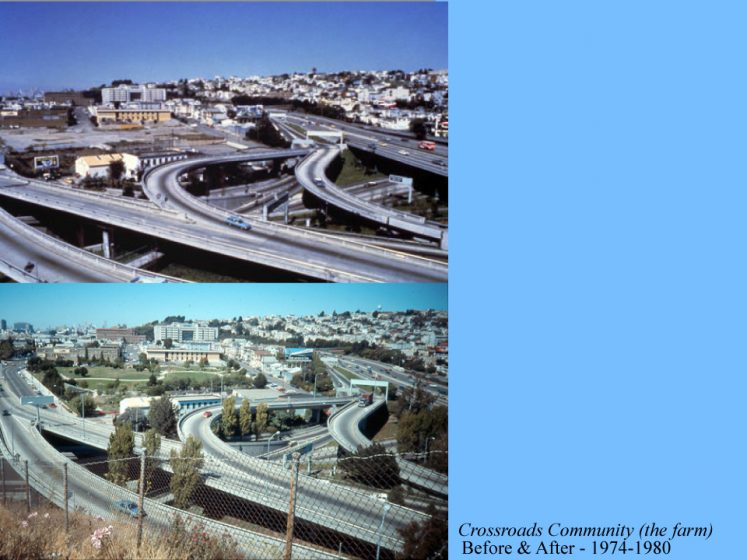

It began as “Sitting Still l”, a temporary performance installation. It evolved into urban agriculture, ecology, multi-arts and education center that transformed acres of derelict land fragments.

At the time, I thought I was demonstrating simply how a seated human could radically transform an environment.

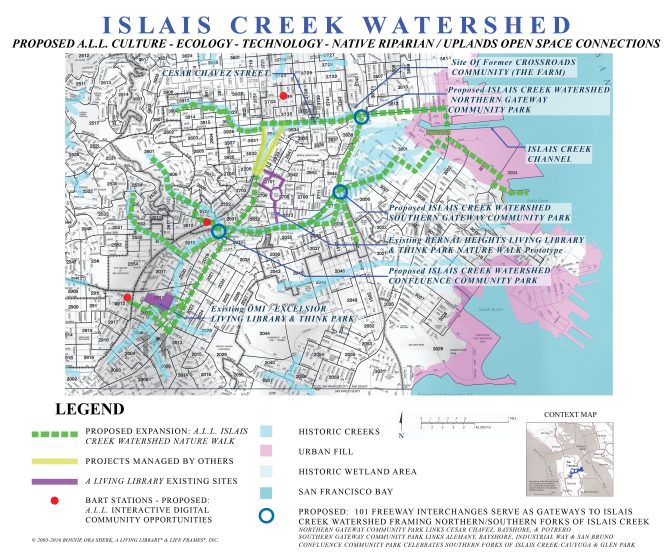

What I did not know, is that I was also facing my future: What would become, beginning in 1974, Crossroads Community (the farm), a pioneering, internationally known, urban agriculture, ecology, multi-arts and education center that transformed acres of derelict, adjacent land fragments including the Freeway Interchange, into a new City Farm Park and one of the first Alternative Art Spaces in the US; the northern frame of the Islais Creek Watershed, which I am still working on—and in—today; the proposed Islais Creek Watershed Northern Gateway Community Park in the currently neglected and flooding 101 Interchange area; and the realization years later, that I had actually been sitting in Islais Creek, water that rose to the surface because of the freeway construction.

Later, in the mid-1990s, I found myself developing the OMI/Excelsior Living Library & Think Park at a four public school, contiguous site (2 High Schools, Middle School, Early Education School) where I had been invited by the Principal of the Middle School to develop A Living Library. During the A.L.L. Master Planning Process that engaged hundreds of students and community members, we discovered old maps that showed the site of Balboa High School, one of the schools, with the Islais Creek flowing beneath it, which had caused massive flooding to the cafeteria which had to be closed, as well as flooding to many homes in the area.

I then realized that I was working in the same Watershed as The Farm, not by design—but through magnificent synchronicity—demonstrating once again, as I had with Sitting Still l, the power of being in one’s alignment, the power of art, and the power of water.

Since then, upstream in the Watershed, the OMI/Excelsior Living Library & Think Park, incorporating my program, A Living Library (A.L.L,), which is a planetary genre of diverse place-based, Branches, meant to be developed world-wide, and interlinked through Green-Powered Digital Gateways, and sponsored by the non-profit I founded and direct, Life Frames, Inc., has taken root, grown, and thrived.

A.L.L. here, over the years, has been working with thousands of students (PreK-12) and community, in hands-on learning by doing, transforming acres of land into ecological wonderlands and Learning Zones that include natives—both riparian and drought tolerant—as well as organic fruit, vegetable, flowers, and herb gardens and other elements.

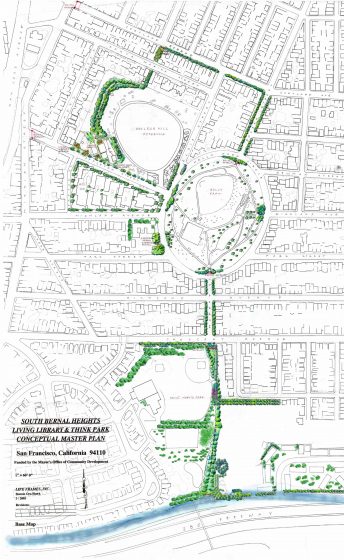

In 2002, I was invited by another school Principal to create A Living Library at her school and neighborhood in Bernal Heights, also in the same Watershed. Through that A.L.L. Planning Process with students and the community, we decided to develop the Bernal Heights Living Library & Think Park Nature Walk that would interconnect diverse community assets – schools, parks, public housing, streets, and other open spaces in the neighborhood through development of a series of resilient native landscapes with interpretive signage, all leading to the currently hidden Islais Creek at the south side of one of the parks.

Now in place, this Nature Walk, with beautiful new native landscapes and interpretive signage, is a prototype for interconnecting the eleven communities of the Watershed, and transforming its two interconnecting 101 Freeway Interchanges into Islais Creek Watershed Northern & Southern Gateway Community Parks, and transforming other flooding freeway right-of-way open spaces adjacent to many flooding homes at the confluence of two Creek Forks, into the Islais Creek Watershed Confluence Community Park.

These proposed places will do many things simultaneously through systemic ecological design: mitigate flooding, create resilient landscapes responding to climate change, make areas safe and accessible, provide community and school education including green skills job training, create habitat for diverse wildlife species, among other interrelated issues and opportunities.

Video: Islais Creek Watershed © 2018 SF Public Utilities Commission and BayCat

The Creek Water and the Watershed have led me and inspired me to do this work, and serve as a natural framework to understand and demonstrate interconnected systems: biological, cultural, technological. The new Gold is Old; it’s Fresh Water!

Nazli Gürlek

Istanbul and Palo Alto

“ONE”

ONE is the choreography of bones, veins, cells, the pineal gland and the spinal chord. This is, ultimately, the choreography of water. Water that flows inside the human body and binds its parts together.

Water is not “urban” or “rural” to me. Water is not this or that concept; it is not separation. It is wholeness, connectedness, oneness. Sacred.

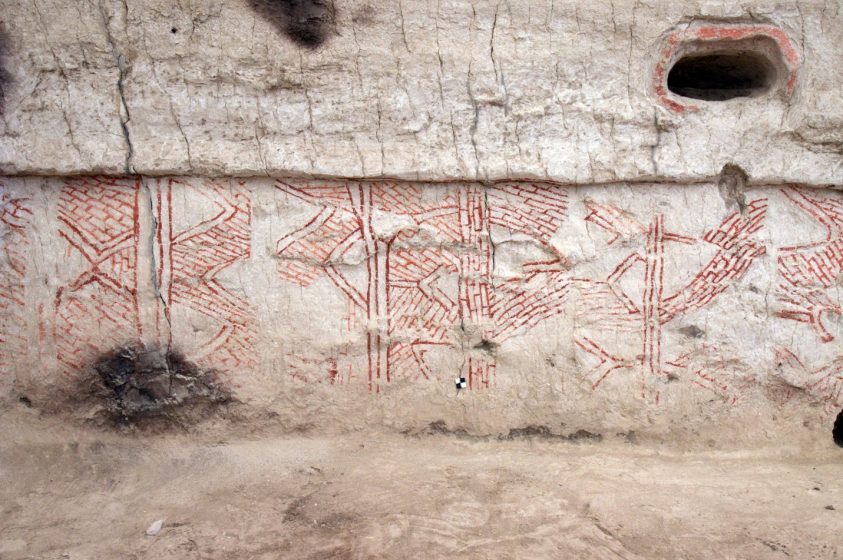

ONE is my performance art piece inspired by a wall painting dated around 6500 BC, discovered inside a house at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük (7,100 BC – 5,500 BC, Konya plain, Anatolia, Turkey).

Çatalhöyük holds evidence of the transition from settled villages to urban agglomeration, which was maintained in the same location for nearly 2,000 years. It features a unique streetless settlement of houses clustered back to back with roof access into the buildings. Its eighteen levels of Neolithic occupation include wall paintings, reliefs, sculptures and other symbolic and artistic features. Together they testify to the evolution of social organization and cultural practices as we, humans, adapted to sedentary life. During my first visit to Çatalhöyük in June 2016 and throughout the meticulous research period that followed it, I have been fascinated by how the society was organised by small routine rituals including a rich production of wall paintings. Art and symbolism seem to have played an integral part in the formation of society. What can we learn from it today, I wondered, and how can we compare it to our own society?

The wall painting that has inspired my performance art piece came to my attention during that very first visit. I was captivated by it at first sight. It was so mysterious yet entirely familiar. Since then I have been contemplating its meaning.

The painting seemed to me to mimic the body—it seemed to move. It seemed to document a process and it was the process itself. It was at once kinetic, volatile, fluid and hollow. It was both abstract and somatic. It reminded me of flesh, bones and nerves; of corporeal vigour. It also reminded me of rivers that flow unhindered; life- giving energy, the power of creation and the boundless source.

The painting was believed to have been created as a part of a ritual. So I created a new ritual to explore its meaning. My ritual brought together four different ways of expression: painting, documentation, movement, and sound. It involved two 9-metre rolls of paper with drawings that I had made in response to the Çatalhöyük painting; visual documentation of the excavation process showing the unveiling of the painting and a live performance based on bodily movements of a performer. A soundtrack based on excavation sounds that I had recorded at the site mixed with sounds of water flows accompanied the performance.

The performance took place last September on an open terrace in Istanbul overlooking the Bosphorus between 5 and 8 pm centering on the sunset at 7 pm. In the course of the 3 hours the painted rolls were gradually unfolded by the performer as she interacted with the paintings with her own body. She had a series of props at her disposal: cordage, five balls with reflective surfaces, and soil in two copper bowls.

ONE is ultimately the choreography of water. Water that unites us with each other and with oceans, seas, rivers and all forms of life that have ever existed and will ever exist. Water that is timeless and boundless reminding us that everything on Earth is just ONE big harmonious whole.

Water is Remembrance

Before art and spirituality became their own concepts, parallel tracks separate from each other as well as from life and Earth, they were embedded together in the way we moved through our days. Spirituality and art were one and the same thing: the sacredness of greeting the sun, the moon and the stars; celebrating the life-giving essence of water, the seasons, the cyclic living and our embeddedness in the grand web of life. This is what it meant to be human –human in a deep belonging and respect for life- and Çatalhöyük could be the unique example of an urban agglomeration based on such principles. Our bodies still carry this imprint. Our bodies remember.

My encounter with the Çatalhöyük painting and the project ONE that stemmed from it is the story of this remembrance. It is the story of my body remembering the currents of communication and reciprocity between all beings and its embeddedness in those currents with every breath. It is the story of honoring the life-giving essence of water as well as the inspiration it has provided –in my opinion– to the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük to make that painting.

Water is not “urban” or “rural” to me. Water is not this or that concept; it is not separation. It is wholeness, connectedness, oneness. Water for me is not a metaphor nor a vessel of dialogue or exchange. It is not a resource, property nor currency. Water is sacredness. It is the experience of my own very intimate embodiment on Earth, the imprint of my being and my connectedness to all other beings. Water is also primeval, preceding and outliving my own little embodied being on Earth. It is what makes my body remember how to be a human, a woman, fully awake to the magic of Earth.

Spirituality and art in the face of water -that runs through pipes in our cities just like blood runs through our veins- are one and the same thing, as our bodies remember, embedded in the way we move through our days. I do see that such growing awareness is awakening cities to the magic of Earth, as it once was, in the times of Çatalhöyük.

Video credit: ONE (2017), Nazli Gurlek, 23 September 2017, 17:00-20:00, Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (RCAC), Istanbul. Performer Asli Bostancı, curator Simge Burhanoglu, sound designer Yusuf Huysal. The performance was held in the context of RCAC’s exhibition entitled “The Curious Case of Çatalhöyük” celebrating the 25th year of the excavations and as a parallel event to the 15th Istanbul Biennial. It was produced in collaboration with Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations and Performistanbul. Special thanks to Prof. Ian Hodder.

Mary Mattingly

New York

Building trends, safety, sewage systems, drinking and agricultural needs have formed and reformed urban waterways. The work I do around urban water is rooted in personal experiences and has expanded most immediately by what I’ve learned about water privatization struggles around the world. I grew up in an agricultural town in the U.S. near Springfield, Massachusetts, where drinking water was polluted with DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethan) and runoff from fertilizer. Without accessible clean water, the people I knew had an acute sensitivity to water as it is connected to human and ecological health. Because water is itself a monopoly (nothing else does what it does for life) and everyone needs the right to water, it cannot be managed by a single entity. Like air, water doesn’t have an alternative. I wanted to co-learn techniques for living in a city acetic-ly, and to envision an urban center that could be less dependent on material supply chains.I began creating interdependent living systems on rivers as a way to share stories about what is possible in urban spaces. I want this work to build coalitions of people who support more public commons, reinforce water as a human right, and who believe in building shared knowledge. Human-created ecosystems offer windows into entire living systems on a scale that is possible for visitors to comprehend and stewards to easily care for: systems with gardens feeding animals and humans, to bees and leftover compost feeding gardens. Since sculptural ecosystems on the water must be contained, participating in them is multisensory. On the water, we need to actively compromise with our neighbors, and we feel its presence as it moves.

In 2006, I wanted to co-learn techniques for living in a city acetic-ly, and to envision an urban center that could be less dependent on material supply chains extracting from rural land, funneling goods through cities, and returning the leftovers to landfills back on rural land. The “Waterpod” was the first large-scale floating, sculptural living structure I undertook. It was to be a habitat and a public platform for assessing off-the-grid living systems on the waterways of New York City. I led a group of artists, civic activists, scientists, environmentalists, and marine engineers in creating the project. Four people lived on the Waterpod for six months. It was a visible public space that created different types of access to New York’s waterways through undertaking a lengthy permit process, multiple ways to reuse and purify water, and through envisioning additional ways more people can steward water as a commons.

Artwork about water is often both literal and metaphorical. Rivers run through cities, yet often as city-dwellers we are disconnected from them. My father grew up running through the tunnels that comprised the Park River underneath Hartford, CT. In the 1940’s the Army Corps of Engineers began to bury it because it was considered unsafe; it was thought to be the cause of multiple floods and pests. Many people who live there haven’t heard of it.

Currently there’s a movement to “daylight” some rivers that run through cities in the United States, as planners learn more about the multiple values of these water sources to the surrounding ecologies. What happens to the quality of a river and our quality of life when we have more opportunities to tend to the water that runs near our homes?

Rivers determine our livelihoods, lives, and the land, and in 2015 I was able to learn more about the rivers of Des Moines, Iowa through working on a project called “Wading Bridge”. With the surrounding farmland tiled to drain extra rain and irrigation water into the river (bringing with it an abundance of nitrates from fertilizers) the rivers that run through Des Moines are a force. “Wading Bridge” was located six inches under water on the Raccoon River. It was a chance to walk with, in, and through the Raccoon River’s rapid watercourse. The idea inherent in this was that crossing it could allow for an intimacy with a river most people would rather avoid than get to know.

To explain a project like “Wading Bridge” is to try to explain the value to both perceptual and physical experience, and the important practice of re-seeing. I wonder if what this revaluing can do for the health of the river, and for its stewardship and care can be profound.

In 2016, I collaboratively formed “Swale”: a public floating food forest in New York City. People can come onto Swale and pick fresh food for free, take part in an event, workshop, or simply visit a floating park. While there, we ask people to engage in pushing forward a local conversation about public food. The experience of being onboard Swale can be uncanny: you feel the movement of the water while watching a land mass covered in perennial edible, medicinal, and pollinator plants rock with the waves atop the barge.

It’s a provocative public artwork, a stage or a tool for strengthening coalitions that work towards more commons in NYC: amidst a glut of privatization we want to insist that not only is water a commons, but healthy food needs to be reframed as a commons too. Places like Swale can shrink the distance between the health of the water and the land, and shrink a gap in access to nutritional foods.

Through Swale, I’ve been able to see how what I’ll call active and provocative artwork can be a folly, a beacon, and can be buttressed and cared for. People from fields of art, agriculture, water conservation, and people who care about fresh food, or clean water, and healthy land all steward Swale in different ways. For me, this work is a reminder that a continued awareness of our interconnectedness leaves us with less room for indifference.

Basia Irland

Albuquerque

I am in love with rivers. And most of the global rivers I have had the privilege to hang out with flow smack through the center of villages and cities. The reason towns are located along the banks of rivers is to take advantage of them for transportation (of merchandise, as a floatation mechanism for wood, and as another “road system” for people), for recreation, and most importantly as a source of potable water.

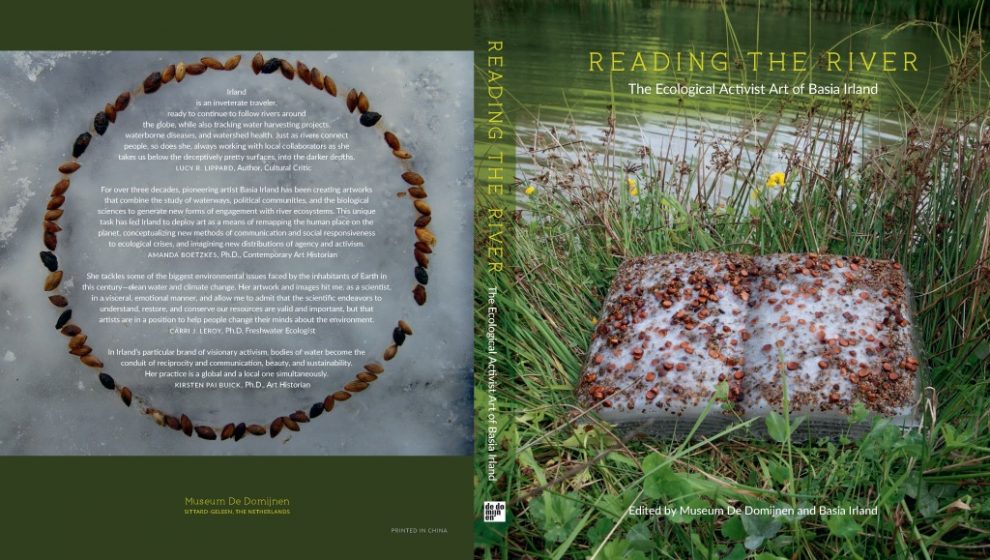

I create projects including “A Gathering of Waters,” which connect communities along the entire length of rivers; and a series (“Ice Receding/Books Reseeding”) that are ice books carved from frozen river water, embedded with an ecological text of native riparian seeds, and then placed back into the stream to foster restoration efforts.

My two books, “Water Library” and “Reading the River, the Ecological Activist Art of Basia Irland” both focus exclusively on international water issues.

I also write a blog for National Geographic about international rivers, written in the first person from the perspective of the water. The few brief excerpts that follow are chosen due to the contrast of how rivers in cities are viewed as sacred, as dumping grounds for every form of pollution, and as concrete conveyance channels. The full blog posts can be read on my website (projects and then blogs).

I look forward to our continuing dialogue about issues of water in cities, which are complex, intriguing, and instructive.

I am the Chaobai River, the city of Beijing’s largest source of potable water. It is a huge responsibility providing over 25 million people with enough hydration to survive! When released from the dam, my water flows for 59 miles (95 kilometers) into Beijing, the capital of China, initially through an open canal, and then part of me enters into iron and steel pipes, so that some of my liquid does not see daylight again until a person turns on the tap, and I emerge into a residential sink, bathtub, or toilet.

Beijing used to have as many as 200 rivers; today very little remains natural about any of my water, as I have been artificially channelized, and managed through elaborate urban planning.

Further discussion will ensue about Chinese “sponge cities.”

On the night of the twelfth lunar month during the full moon at the end of the rainy season, communities gather along my banks to pay homage to me, and my water spirits.

This festival of lights is called Loy Krathong (ลอยกระทง). The name is translated as “to float a basket,” and refers to the tradition of making krathong or buoyant, banana-stem sculptures that are decorated with folded banana leaves and contain flowers, incense, candles, and coins (an offering to the river spirits). These sculptures are floated on my moist skin in the evening forming a candle-lit parade dancing downstream.

I am clogged with human ash and bits of bone. I have always borne the remains of the dead, who are taken to the Pashupatinath Temple on my banks near Kathmandu, Nepal, placed on pyres, ignited, and blessed in Hindu ceremonies. The cremated are swept into my murky waters to plod along toward the confluence with the great mother Ganga as I join other tributaries downstream.

My primary role is as a source of spiritual salvation for millions of Hindus, who take a dip within my waters. And yet, at this particular site, my plight has been the same for decades — an open sewer, full of garbage from an ever-increasing population. I try to flow, but really, I just slog along. There have been gallant efforts by local valley dwellers in recent years to try and clean my body and rid my ribs of slush and guck, but it is an overwhelming task.

I flood. That is what I — and all my cousins — do from time to time. It is part of our rhythm. In their hubris, humans build cities and towns right on our banks, then get upset with us when our waters rise and destroy some of their property. They try to control us by building dams and straightening our courses so that we no longer flow naturally, aiding the hydrologic cycle, creating meanders, spreading silt, and sustaining entire ecosystems of aquatic life, plants, and animals.

It is a sad tale of how people cannot think of me as a living being, but rather as a nuisance. Here is how they have mistreated me: They have encased my body in 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers) of concrete, putting me in a straightjacket so that there is nothing natural about me anymore. I am not even called a river, but rather a “channel”. Locals sometimes refer to me as “the moat” or “the bunker”.

I have heard that some communities are not very friendly to their rivers, but many friends everyday walk the paths along my shores, ride bikes, have picnics, push baby strollers, and bask in the colors of the nearby trees with cherry blossoms in spring, and red maple leaves in fall.

Any visitor to this city will notice a lot of plastic trash floating on my surface, and there are currently attempts to clean up my 60 miles (97 kilometers) of canals. One such venture, Plastic Whale, is a company that fishes plastic bottles and other debris from my water and transforms the trash into material to make a boat that will be used to fish for more plastic. Boat Number Seven is constructed from over seven thousand plastic bottles that might otherwise have found their way out to sea.

Aloïs Yang

Prague

It all begins with listening.

I am a sound and media artist, who spent most of my life time in cities. Urban sonic environment can often be overwhelming, saturated with sonic informations constantly coming at us. Consciously or subconsciously we all build multiple protective filters so to only receive what we want to hear. In my experience, these passive listening processes take a lot of unwanted attention and energy. Instead of looking for calm places or for some silence that does not exist, I developed a habit of “listening meditation”. It is a practice to free my mind from thoughts and to focus in the present. I treat all sounds equally and appreciate them as they are. By opening up my whole sensibility to a certain level I reach a point where I am able to expand and lose myself freely as sound in space. This practice enables me to observe the ever-changing time perceptions offered by the movement of sound. These inspiring moments often lead me to produce new creations based on field recordings. This is how my interest for water and sound began, in artificial surroundings. How can a tiny event—a drop of water, or the sound of cracking and melting ice—create feedback loops that eventually can be seen as the whole? Every aspect inside a system is connected to others and capable of revealing the bigger picture.One of the most intriguing discovery I made is that water has the sonic ability to reflect human activities in harmony. It absorbs the directional forces that we push towards our goals and makes things slow down. It reminds us to humbly live with nature.

Some of the first expressions of this work resulted in “Fluid Stones in the Garden” and “Ping Pong Spring Waves”, two recordings based on a “urban meditative sound walk” i did in Vienna, in the Spring 2017.

It was followed by “Micro Loop Macro Cycle”, a series of installation, performance, video, and sound production that investigates environmental cycle system through studies of different states of water. “Micro Loop Macro Cycle” is an ongoing project, that took place in the cities of Turku, Finland and London, U.K in 2017, as well as in the Brazilian’s jungle in 2018.

Sound and water are the primary materials of this project. Sound is used as the communicational medium revealing comprehensive sonic informations about the dynamic states of present time and space. While water, the most common substance on Earth, carrying life and present in almost every biogeochemical cycle systems, is used for this very capacity to highly connect to its surrounding conditions: from large scale environmental changes to small molecular scale variations, from energy waves to shifts in chemical substances. Through the understanding of these notions and the observation of water, we gain insights on systematic interactions. It provides us with measurement and connection, indicating our relationship with nature.

The focal point of this project is to present how a tiny event—a drop of water, or the sound of cracking and melting ice—in a given cycle system, creates feedback loops that eventually can be seen as the whole. I also want to show how every aspect inside the system is connected to others and capable of revealing the bigger picture on its own.

Installation

Video: Micro Loop Macro Cycle – in 4:16s & 363mb” Recorded at Titanik, Turku, Finland 2017

Video: Micro Loop Macro Cycle – in 5:13s & 425mb” Recorded at Cafe Oto Project Space, London U.K., 2017

Performance

Video: Micro Loop Macro Cycle – in 24:50s & 2940mb” Recorded at Resilience: Artist in Residence by SILO, Brazil, 2018

Sound production

Based on the recorded materials of “Micro Loop Macro Cycle”, I positioned myself as a studio artist. With the aim of contrasting and balancing between two realms, one is the realm of nature – to obey and reveal the organic sonic informations created by natural phenomena. The other realm is the presence of consciousness – the search for humanistic aesthetics in the form of minimalistic improvisation. This soundtrack will be released in July 2018, on the sound art label and explorative platform 901 editions. For more detailed information about the project please visit here.

During the journey of making “Micro Loop Macro Cycle”, I understood that the most important thing I aim to do with this work, is to raise awareness on the separation we consciously create with the nature realm. When I position myself as the observer, researcher, or artist, I understand that realm intellectually, and establish relationship based on my needs. For instance, it took me few try and fail to understand how to freeze the ice with higher transparency, for aesthetic reasons in the installation set-up. And not to mention the cognitive works I did by using technology to achieve my artistic visions. On the other hand, I had experienced my capabilities to connect with nature in the unconscious, when mind and body are not separated. This beautiful moment happened during the river performance at a rainforest in Brazil, when I place myself in the state of wholeness, when the actions of art disappears, when I eventually became one within.

I don’t see these two relationships with the nature as a conflict, on the contrary, I see shifting these two states of consciousness as forms of resilience in responds to our ever-changing environment. I believe this human-being quality of incorporation between mind and body, inner and outer, to the natural cycling system will be more and more important in our time of high information and technology exposure, and online virtual reality. Especially in the fast urban lifestyle, where the natural forces are hidden or disguise as products, it is much more complex to feel and work instinctively with these natural states of transitions. I see that the challenge in our daily busy life is to answer the question – how do we identify the pure nature within ourselves? To reconnect with our surrounding nature as much as possible, from one small drop of tap water, to an vast ocean. And how to be flexible and stable at the same time? To cycle through dynamic states of mind, circumstances and conditions we have to face, in a seamless, formless, and effortless way, just like water.

Nadia Vadori-Gauthier

Paris

Dancing water

Water, with its physical properties, is a primordial element of my dance and performance practice, in relation to movement, rhythm, space, and life itself. To begin with, our bodies, like that of the Earth, are principally composed of water. For us, proportions vary from 75 percent water for a newborn to 50 percent for an old person.

Water has several fundamental characteristics:

- Relationship to life: It underlies all life in matter. On the Earth, no life is possible without the presence of water.

- Relationship to movement: It is mobile and may take different forms. Its plasticity allowsit to change unceasingly. Water travels, espousing and shaping the territories it passesthrough. Its trajectories are often curved or spiral, with a certain unpredictable quality.

- Relationship to the earth: It has a weight and pours towards the earth with the force of gravity.

- Relationship to space: On the other hand, it has a quality of capillarity, ascending,

plantlike, which allows it, for instance, to rise along a strip of cotton or expand towards space in every direction, like the surface film of a waterdrop. - Volumetric quality: Between these two antagonistic and complementary forces of gravity [3] and anti-gravity [4] there opens up a multi-directional volumetric space, with no hierarchy among its various parts. To draw a parallel with the dancing body, for instance, this quality allows a body to be lived “in 3D,” moving in multiple directions, as opposed to a vertical body seen in “2D,” with a front and back, a top and bottom. This summons an “immersive” dimension of feeling, rather than an overview, distanced or separated from consciousness. When one dances from this fluid base, consciousness accompanies movement. It precedes or derives from it, inseparable from lived experience.

- Rhythmic quality: Obedient to forces of propulsion or aspiration, it behaves dynamically, creating patterns in movement: waves, vortices, fluid rhythms. In our bodies, our liquids have different rhythms. They rebound in our membranes.

- Quality of resonance: Water is an element that captures and preserves sonic or

mechanical vibrations and arranges them in natural models (as in cymatics) [1].

These qualities of water, allied with my experience of dance, both in the studio and in nature and the city, greatly influence my way of entering into contact with people and environments. They lead me, through sensation, to enter into a non-hierarchical and non-anthropocentric relationship with earth and space, but also into vibratory resonance with places and materials of my surroundings or with the natural elements.

For the project One Minute of Dance a Day, I created some hundred dances involving the element of water. But even when water is not visibly present in my surroundings, the body out of which my dances begin is principally liquid, moved by a fluid dynamic. By taking as the basis from which my work begins the fluid matter of the body and its cells, I realized that I enter differently into resonance with places and things. I find an alliance with what surrounds me.

Video: Dance 1186 (One Minute of Dance a Day), Nadia Vadori-Gauthier / April 13th 2018, 11:12 a.m., calle de la Racheta, Cannaregio, Venice, Italy.

BMC®

This particularity is also one of the characteristics of my practice of Body-Mind Centering®. This practice was created and developed by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, dancer, researcher, dance teacher, and ergotherapist whose practice combines yoga and martial arts. Contrary to other practices of somatic education, this is neither a technique nor a method. Its tools are extremely precise and refined, but there is no particular protocol to follow. Unlike techniques such as Feldenkrais and Alexander, which most specifically consider the muscular-skeletal system, BMC, like Continuum Movement, is based on the experience of the body at a cellular level and a somatic training in fluid movement. Through movement and touch, the practice favors the lived experience of flux physics, that of a fluid base taking as reference the constant navigation of all things. This particularity influences my research. In effect, the body is not envisaged in the perspective of fixed form, identity, or posture; it renews itself constantly within a larger flux. It does not merely travel through space, it transforms itself, without changing place.

The body’s fluids (cytoplasm, interstitial fluid, blood, lymph, cerebrospinal fluid …) are differentiated by movement and touch. They have different expressions, rhythms, densities. The soma of BMC is a fluid body-mind with its cells. There is fluid within the cells and fluid outside them. The exchanges between intra- and extracellular fluids are the liquid respiration of the body: cellular breathing. It takes place in all the tissues: bones, organs, muscles, etc. A cell is a system in constant evolution that records innumerable molecular variations. In this context, it is the metaphoric base of a vibratory resonance common to all that lives. From this vibratory substratum, still formless, there open out new sensorial territories, spaces of resonance by which new forms may be generated.

For the past twelve years, my explorations have progressively led me to address my artistic processes through the sensation of the organism’s fluids and the cellular breathing of the tissues. This brings about a base, in constant motion, from which I enter into dialogue with the elements, places, and things. I find an alliance with materials. My body goes beyond its own organic form to adjust to its surroundings in a vibratory, almost musical fashion, forming harmonies or dissonances. These vibrations include light, space, and color.

This practice establishes modes of corporeality and interrelations that involve a primacy ofmovement and lived experience of the living body, in relation to other bodies and its surroundings. This specificity is essential to my work. It generates its own modes, at once single and collective, non-hierarchical. It brings about a focus on process rather than form, it enters into flows and rhythms rather than focusing on an object. It is, for me, a practice of individuation, of becoming, the creation or reorganization of the self. It facilitates an intersubjectivity that welcomes difference, distance, decentering. It arranges the collective horizontally, encouraging freedom of rhythm and movement in each element.

In the city, more than elsewhere, it seems important to me that we remain connected to nature and its elements, including water, the basis of life and its constant fluctuation. Cities that rivers run through, cities beside the ocean, cities refreshed by fountains or canals, have a special sweetness inviting to reverie and the imagination. The movements of the surfaces of water make the reflections of the sky and the world around them dance; they move them and give them rhythm. Thus the geometric lines of buildings and spatial perception become more sinuous or undulatory. They voyage and thought ripples along with them, opening our senses to constantly renewed possibilities for movement. This fluidity keeps us connected to the forces of life and imagination. It allows us to reinvent ourselves in connection with each other, tracing moving and inclusive lines between our differences.

Video: Dance 579 (One Minute of Dance a Day), Nadia Vadori-Gauthier / August 14th 2016, 10:05 a.m., Water Mirror, Quais de la Garonne, Bordeaux, France.

Video: Dance 558 (One Minute of Dance a Day), Nadia Vadori-Gauthier / April 15th 2016, 3:12 p.m., Duranti street, Paris 11th, France.

Even in the absence of water, every day I dance the water of cities, the water of our bodies, and their rhythms of fluid pulsation. I am sometimes accompanied by figures that influence my imagination and my dances; among them: Dionysus and Shiva. These two divinities are said to have a single origin. They are both masters of the fluid 2 element and of metamorphoses, as well as masters of time, particularly of a cyclical, tidal time. They are thus profoundly connected to wild nature and its cycles of life/death/life. In spring, water and sap rise up in stalks; nature flowers. Then does Dionysus appear, presiding over the rite of blossoming. All around, water is with us in the trunks and branches of trees, in plants, flowers, and all their vegetal manifestations. To dance water is also, for me, to dance in cellular resonance with the dynamic fluid movement underlying vegetal forms; it is to dance with humans and animals, dance in rain or rivers; dance the pulsing blood in arteries and veins.

The liquid dimension of experience allows me to be in relation to the world. This relation is vibratory and solidary. Water, in me and outside me, connects me to life and nature. Thisdimension of experience, which I explore alone and in a group, particularly with le Corps collectif (The Collective Body), contributes to what Antonin Artaud called “healing life” [3] by restoring its fluid poetic forces to a life that the modern world has drained of its powers.

Video: Dance 182 (One Minute of Dance a Day), Nadia Vadori-Gauthier / July 14th 2015, 11:20 p.m., Saint- Michel place, Paris 6th district, France.

Notes:

[1] “La vibration est à l’origine de toute forme,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=beJQYFSbmt0 , in Mondes intérieurs, Mondes extérieurs – Partie 1 – Akasha, a film by Daniel Schmidt, REM Publishing Ltd. Film (Responsible Earth Media Ltd.), 2009.

[2] David Smith, The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South of India, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

[3] Antonin Artaud, Le Théâtre et son double [1964], Paris, Gallimard, « Folio », 2009.

Marguerite Perret

Topeka

Love, Ice and Tourism in Reykjavik

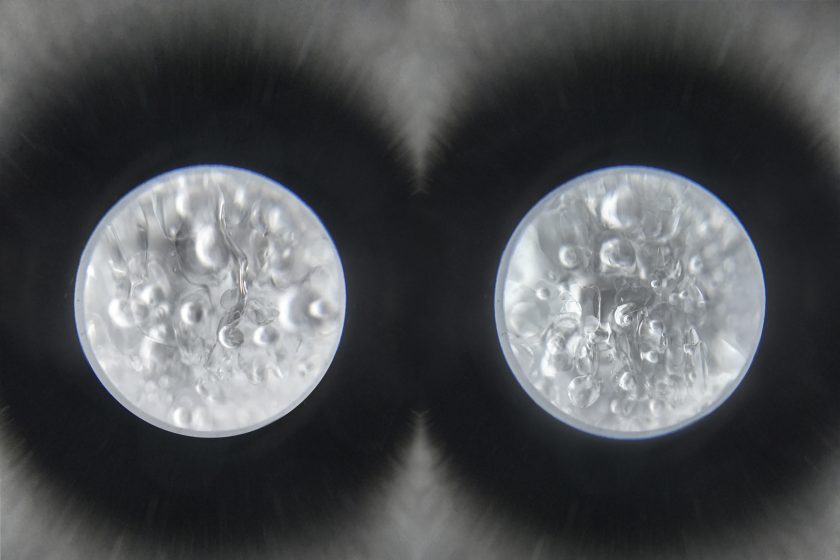

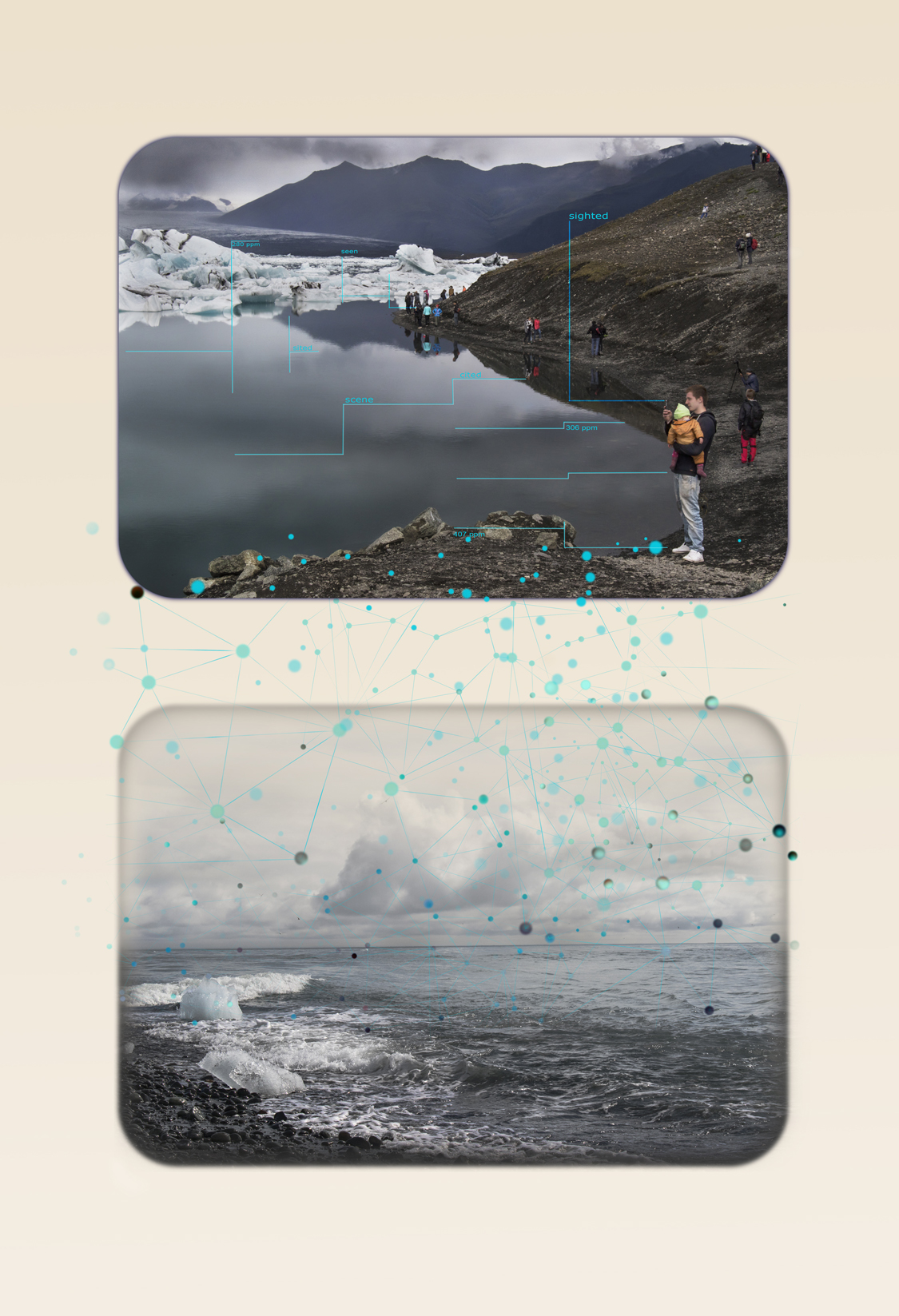

Tiny bubbles. Air trapped in glittering chunks of ice on black sand, the remnants of icebergs broken away from the mother glacier and torn apart by turbulent waters at the mouth of the Jökulsárlón lagoon. Some are small as a fist and others large as a tour bus. Most drift out to sea, but others languish on the beach quietly liquefying, providing the 2.3 million tourists who visit Iceland annually with another spectacular selfie moment. If you look closely, you can see rivulets of water under the surface collecting in air pockets like tears, as if the ice is crying from the inside out.

The Snæfellsjökull glacier, visible from Reykjavik, is disappearing. Vatnajökull and Langjökul glaciers may be gone by the end of the century. Climate change will be challenging here as everywhere. But Iceland is not Iceland without glaciers.

These bubbles are miniature atmospheric time capsules. Glacial ice stores information about climatic conditions dating back tens of thousands of years held in the captive breath of ancient forests, Vikings and volcanoes. Analysis of carbon dioxide levels in ice core samples evinces increases from 250 parts per million (ppm) in 1900 to 407 ppm in 2017. Correspondingly, 2017 was among the warmest years on record.

The Jökulsárlón glacier lagoon sits at the base of an outlet glacier of the Vatnajökull in the south-east part of the country. It is the largest glacier in Europe. Hundreds of daily visitors are enchanted by the luminous aquamarine ice and blue water, but most don’t make the connection that the lake is a symptom of an accelerating thaw that expands annually.

Four hours to the west the capital city of Reykjavik is benefiting from a booming economy driven largely by the tourist industry. It is the portal to the country’s natural wonders such as Jökulsárlón which can be accessed by an all-day round-trip bus tour. The famous Gullfoss waterfall, which is fed by the Langjökull glacier, is even closer at only an hour and a half drive away. The Snæfellsjökull glacier, visible from Reykjavik, is rapidly disappearing. The larger Vatnajökull and Langjökul glaciers may be gone by the end of the century. Climate change will be challenging here as everywhere. Rising seas levels, changes in precipitation and an increase of volcanic activity—are all possibilities. But one thing is clear. Iceland is not Iceland without glaciers.

Tourism, either directly or indirectly, drives much of the city’s cultural innovation and employment opportunities. Clearly the presence of too many humans disturbs fragile ecologies, trampling surface vegetation, polluting water and soil, and spreading invasive species. But if the opposite of love is not hate, but apathy, the people we met were passionately in LOVE with these places, reinforcing our contention that personal experience with non-human nature is essential to conservation.

And of course, Icelanders love this landscape best of all. Reykjavik has committed to go carbon neutral by 2040. Is it too late?

Can love save the ice caps?