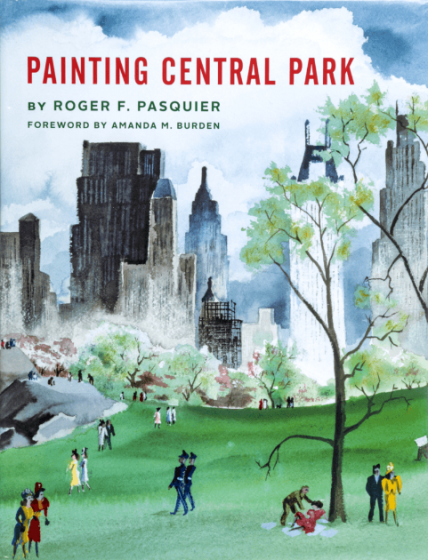

A review of: Painting Central Park, by Roger Pasquier. 2015. ISBN: 0-86565-314-3. Vendome Press, New York. 197 pages. Buy the Book

For the past two years, I’ve invited people to pick free food on Swale, an edible public park built on a barge in New York City. Creating something unexpected is a technique that I’ve utilized on Swale to frame an engaging experience where visitors feel like they are on land and on water at once. Such an experience helps to connect visitors with common spaces in unusual ways. Reading Painting Central Park convinced me that, although a term usually reserved for ornamental architecture that is out of place, parks in cities are all follies to an extent. Through being out of place they insist we confront difference. Artists who paint the landscape inside of the city are drawn to these differences.

Throughout the book, artists’ interpretations of Central Park range from abstract to diaristic and photorealistic. The selection of artwork propels the reader into the book, and acknowledges how some of these images may inform our own cultural imaginations of the park, a park that has been a site of modern pilgrimage, a subject of many films, novels, and photographs that have circulated near and far.

For over a century New York’s Central Park has been a muse for artists.

With a preface by Amanda Burden, who asserts that it’s a human necessity to be able to engage with flora amidst urban street life, Roger Pasquier writes an homage to Central Park. He traces the history of the park through the original Greensward Plan, created by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. He describes the landmarks, buildings, and landscapes that were designed to be intentionally anomalous. Olmsted and Vaux’s plan utilized strategies from English landscape design, such as incorporating follies and other architectural structures for visual interest, while also embracing the grandness of the Catskills to the north. In 1858, 3,800 workers were employed to recreate what Olmsted and Vaux perceived were the better qualities of the less-colonized Catskills nearby.

Pasquier shares documents and accounts that evidence the architects’ obsessions with creating tension in a park visitor’s experience. They did this by framing Central Park’s multiple access points as a series of idealized viewsheds into the park, based on what catches peoples’ eyes, and what a painter may choose to paint.

With admiration, he takes us on a journey through some of the many artistic representations of Central Park via visual artists who made the 843 acres of hills, lakes, vegetation, and visitors their muse. We move from Jervis McEntee’s View In Central Park, 1858 (a stark meadow with scattered boulders) quickly to the more active paintings of Julius Bien. As Central Park grows into itself, the paintings and literary references describe a more communal place. That transition is described by two quotes from Henry James who witnessed the park shift over time. His first visit to the park was translated for his novel The Bostonians (1886) with “lakes too big for the landscape and bridges too big for the lakes”. Later in 1905, James observed:

The variety of accents with which the air swarmed seemed to make it a question whether the Park itself or its visitors were most polyglot. The condensed geographical range, the number of kinds of scenery in a given space, competed with the number of languages heard, and the whole impression was of one’s having but to turn in from the Plaza to make, in the most agreeable manner possible, the tour of the little globe.

From paintings of major landmarks like the Bethesda Terrace, to crowds ice-skating, and people in solitary contemplation, Pasquier helps us see a variety of different perspectives of the park. Reproductions are organized thematically, into sections with titles such as “The Park’s First Artists”, “Celebrations and Quiet Times”, and more. The selection of artwork propels the reader into the book.

From painters difficult to categorize such as Rackstraw Downes to the abstractions of Milton Avery and Helen Frankenthaler, or the photorealism of Richard Estes, Pasquier curates a voyage through time, power, beauty, and imagination. Pairing David Hockney’s View from the Mayflower Hotel, New York (Evening), 2002, next to Marc Chagall’s Vue de la Fenêtre sur Central Park, 1958 show artists as voyeurs and subjects; both chose to paint Central Park from windows inside of their rooms looking down on it.

The last chapter highlights the idea of the frame again, but this time it’s not the frame around the canvas or the perspectival views outlined by the park’s planners. Pasquier wants us to see the entire park as a painting, to picture Central Park from above, to imagine its vistas flattened and abstracted like a satellite image of the park, until we are indeed seeing a work of art meant for the wall. Perhaps my favorite chapter, because Pasquier asks us to suspend our belief in Central Park as Central Park, but rather to understand it as a painting too. We can imagine zooming upwards from the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a satellite view of the entire panorama, and then imagine that the Art Deco, Beaux-Arts, and Neoclassical buildings that immediately line the park are the first indentation of a Baroque frame. For blocks, we witness the wealth of this frame, every square foot ascribed extraordinary economic value, but then we are brought back to its focal point, Central Park, whose value can never truly be quantified.

In 1862, Harper’s Monthly said of Central Park, “the finest work of art ever executed in this country”, and the park draws admirers worldwide. Roger Pasquier grew up with Central Park. The idea for Painting Central Park came to him when he was working with environmental organizations in Washington, DC. He writes, “[t]here, nothing made me more homesick than looking at George Bellows’s Bethesda Fountain at the Hirshhorn Museum”.

In the summer heat, I hold my breath while looking at a representation of Guy Wiggins “Central Park Skyline” in wintertime, and realize it could encapsulate my own love for New York: the brilliant warmth and camaraderie from within the cold. I find myself yearning to be transported to Central Park, too.

Multiple cultural imaginations exist of Central Park, and this book is a gateway into some of them. As a good book tends to do, it leaves me wanting more. I look forward to a follow-up, part two of Painting Central Park, when Pasquier may take Jean Claude and Christo’s “The Gates” as an entry point to investigate some of the expanded fields of art. These could include both representation and active art, moving images and performances that are site-specific, or that Central Park is the main protagonist of. In a crowded city, a park is a landscape of difference. For over a century Central Park has been a muse for artists. These artists inform a growing cultural imagination about it.

Mary Mattingly

New York

To buy the book, click on the image below. Part of the proceeds return to TNOC.