Introduction

We believe that urban green spaces and natural resources have value. Much of the writing at TNOC describes urban open space, in its various forms, as one of the key drivers of cities that are more resilient, sustainable, and livable. But who manages urban open space and natural resources? Who “owns” them? Who gets to have access and use them? Who is “responsible” for them? Who decides how they are used? Is it the community that lives next to them, or the entire city (which usually means the city administration)? Answers to these question relate to a fourth key theme at TNOC: creating cities that are just.

These issues are embedded in distinctions between “public goods” and “common pool” resources. Central to the definition of a public good is that it is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. That is, everyone has access, and one person’s use does not prevent another person’s use. (The use of an item of food is exclusive—when I eat that apple, another person can’t. When I build my house on a wetland—lucky me—but the other public values of that wetland have now largely been consumed.) Examples of public goods include (ideally) the air we breathe, roads, parks, systems of stormwater management, the enjoyment of birdsong. Common pool resources are owned (and sometimes managed) collectively by a community or society rather than by individuals. Some classic examples are fisheries, forests, and community gardens. The benefits are open, but they can also be used up (potentially resulting in “the tragedy of the commons”). A third category is private resources, an idea of “property” that is common in modern economies (but not necessarily traditional or indigenous ones)—an idea that can easily be at odds with the benefits of both public goods and common resources.

In the real world, in the context of urban natural resources and green space, these can be broadly overlapping or even confusing distinctions. But the underlying ideas are important to how we create green cities. Conflicts between these very different conceptions of to whom the “goods” of urban nature belong and how they are managed are fundamental to many urban contestations: for example, the conversion of wooded streets to concrete highways or wetlands to commercial real estate; inequitable distributions of nature-based solutions to social challenges, such as resilience to storms; foraging in public parks; community gardens in vacant lots; or habitat destruction that leads to loss of biodiversity. They relate to how cities spend money in different neighborhoods. They relate to the emergence of public-private partnerships as a mechanism for public space management. In the Global South, there are cities in which green spaces are consumed by nominally public streets or buildings, or privatized into clubs behind members-only gates, leaving no green spaces for ordinary or poorer residents. In New York, there are are examples of developers given zoning variances in exchange for providing “public spaces”, but public access is subtly (or not so subtly) discouraged.

These are real and deep issues for green city building. To whom does the city, including its green spaces, belong? How is it used? And who decides?

Lindsay Campbell

I’m going to sidestep the theoretically rich domain of defining what we mean by “nature” in the “city” and focus in on the narrower subset of urban nature that occurs on the land, including vegetation and green space. So, I’m not considering the atmosphere, water, or energy systems that further constitute our urban environment and that can variously be considered as public goods or privatized commodities.

We need to cultivate place attachment and cohesion that emerges through community self-help, while also supplying crucial municipal resources to support—but not stifle—that engagement.

There is a spectrum of governance arrangements on the land—from the quintessentially shared community garden to the sometimes-exclusionary private lands. But for the most part, every piece of urban land is some shade of gray, some mixing of the public and the private. Plazas, parks, sidewalks, subway platforms, stoops—whether privately owned or publicly managed—they are part of the public realms, spaces where people, at least visually, if not physically, mix. So, while our property jurisdiction may subdivide the land into discrete parcels, we as humans moving through space can experience it as a blurrier, more complex, and multilayered system. Claims on land are both overlapping and incomplete—authorities are never total.

Over the course of my research, I’ve investigated grassroots management of green space, from community-based natural resources management in rural, Global South contexts to community gardens in urban, Global North contexts. I’ve always been drawn to bottom-up, community-led environmental management and have sought to understand why and how people engage in stewardship of the land. This is because I believe in the power, creativity, and voice of communities to solve problems locally and manage landscapes in ways that meet their needs, including through acts of commoning. Along with my co-editor, Anne Wiesen, I explored some of these ideas in the edited volume Restorative Commons: Creating Health and Well-being for Urban Landscapes.

We often see the emergence of community-led solutions in the retreat of capital or the absence of government. In 2005’s City Bountiful, Laura Lawson wrote about the history of community gardening in America and its relationships to periodic crises: the Depression, World Wars, and financial declines. This pattern continues to the present, as we see shrinking cities and Rust Belt cities that are simultaneously wellsprings of community farming, homesteading, and arts practices. With disinvestment by public and private authorities, we see people making their own claims on the land, not only through gardening, but also through squatting and other forms of individual and collective empowerment and self-help.

Though we see innovation and bottom-up management during moments of crises, how can we foster community stewardship in the “good times”? In the current context of New York, where I live, and in many other cities around the globe, community land management practices can be enabled by public authorities and private resources. As such, my more recent research for the book City of Forests, City of Farms (Cornell University Press, September 2017) examines the networked governance of urban forestry and agriculture. I find that municipal parks departments and private NGOs play important roles in supplying access to land, basic material inputs, and labor to organize community residents. For example, the NYC Parks GreenThumb Program has existed since 1978, and provides support to approximately 20,000 community gardeners citywide. While gardeners are the primary land managers of their sites, they adhere to minimum rules of conduct, open hours, and membership policies and also have access to soil, plants, other materials, and trainings as part of the GreenThumb network. We also see examples of public-private partnerships (for example, the MillionTreesNYC campaign), land trusts (such as The Trust for Public Land), and community coalitions (New York City Community Gardening Coalition)—all as different forms of governance arrangements involved in the stewardship of urban environments.

Effective and equitable management requires a balance. We need to cultivate place attachment and cohesion that emerges through community self-help, while also supplying crucial municipal resources to support—but not stifle—that engagement. And further, given the intense competition for space, in the context of skyrocketing real estate markets in many cities, we must find space for individual expression and collective action. Can we leave a little space, something a little more “wild”, a little less “governed”, in order to see what emerges?

Work cited

Lawson, Laura. 2005. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Amita Baviskar

Common Pool or Public Good—What Matters is Environmental Justice!

In Delhi, the city where I live, nature is an accident. The heart of India’s capital may have stately avenue trees and sprawling gardens, even an “urban forest”. But the rest of the metropolis is an arid expanse of concrete and asphalt. In the packed warrens where the poor and lower middle classes live, there’s little space for nature. At least, not nature as most city-dwellers know it—no parks and pastures, no lakes and streams. The green and the blue have been consumed or conscripted to serve the city. The streams carry away sewage. The pastures have been converted to plots with higgledy-piggledy housing. And no one cared to leave space for parks.

The city in the Global South is a hard place for nature and for poor people—they find the in-between spaces. For biodiversity and for human rights, we need more vigorous democratic politics.

So nature survives by chance. On derelict strips along railway tracks, on abandoned lots tied up in litigation, on swampy soils along the river where it’s unsafe to build. This is where a family of Grey Partridge scuttles into the protective cover of heens shrubs. Where the Small Indian Mongoose darts like a golden streak into a clump of wild grasses. Where Black-headed Gulls swoop in from Siberia to the river Yamuna’s sludgy waters.

This nature was not planned. Plants and animals simply occupied every ecological niche that they could cling to or claim. It’s human neglect, not human design, that allows them to go on living.

And it is in these in-between spaces that the very poorest of citizens, too, make their homes and their living. Take the stretch of land along the river Yamuna. Farmers grow melons and radishes on alluvial islands. Washer-people spread clothes out to dry on the banks. Goats fattened for sacrifice on Bakr-Id are rested and watered here, amidst thickets of white-plumed kaans grass, on the way to the Jama Masjid market. Upstream, Hindus pray and perform rituals to honour the dead. This is where people from the squatter shanties on higher ground descend to defecate, groups of veiled women walking down at dawn and dusk.

Some of these practices are long-established, others newly negotiated. But whether old or new, legal or unlawful, unspoken or boldly asserted, they constitute customs about the commons, carved out as much by encroachment as by the continuity of old usage (the farmers and washer-people have legal rights; the squatters, who are mostly migrant workers, don’t). And yet, these commons have only survived because governments and developers have so far found them valueless. Fugitive flora and fauna could flourish and hard-pressed migrant families could find homes only as long as this sandy stretch remained invisible in the eyes of developers. When the riverbed became real estate—as started to happen with India’s economic liberalization in the 1990s—and the commons became convertible into cash, the customary practices that they supported were cut off. In 2004, 400,000 squatters were evicted from their homes on the river’s embankment. Many farmers’ leases were terminated soon after.

But wait! Before you think this is the old familiar story of “the commons versus capitalism”, consider this: both these moves were ordered by the Delhi High Court acting in the public interest. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court of India also invoked “the public interest”, but to retrospectively legalize a gigantic temple complex on the riverfront. A few years later, the same court allowed luxury apartments to be built on the floodplain, even though both these developments disrupt groundwater recharge and release effluents into the river. “Public interest” or private profit and privilege?

Double standards often prevail when environmental conflicts occur in a society as unequal as India. For our courts—guardians of the public good—“saving the river” meant kicking out the migrants who crowded its banks; never mind that the water is mainly polluted by untreated sewage coming from well-to-do neighbourhoods. But prestigious projects gleaming of high finance and sleek aesthetics are allowed to override environmental concerns.

It’s not just the courts that harbour such views. So do bourgeois environmentalists—well-connected citizens’ groups that profess to be nature-lovers but who do little to lighten their own ecological footprints. For them, nature isn’t a means of subsistence or shelter. It’s a lifestyle accessory, a place of pleasure and recreation. They desire an ordered, domesticated nature, preferring manicured gardens over wilderness, riverside promenades over fluid floodplains. The problem is that these vocal and well-organized groups dominate debates about defining the “public interest”. And their power means that poor people’s predicament is made illegitimate and their claim to environmental goods—safe shelter, water and sanitation—is ignored.

The city in the global South is a hard place for nature and for poor people. For biodiversity and for human rights, we need more vigorous democratic politics. Only that will enable the marginalised and the excluded (and their representatives) to drive decision-making towards environmental justice.

Marianne Krasny and Michael Sarbanes

A Tribute to Jill Wrigley

What happens when nature in the city runs counter to what we think we know about common pool resources and public goods? When we observe urban nature that challenges common creeds, such as:

- When common pool resources are owned by governments or communally they become public goods, but when owned by private individuals they are private goods.

- Restricting access and assigning individual rights to a resource stops people from destroying common pool resources.

- Without specific government policies, public goods will be limited [1, 2].

Baltimore, Maryland is a far remove from Sweden. Yet, inspired by the Swedish tradition of farmers allowing anyone access to walking on their land, a Baltimore family bought a house with a wooded yard bordering a stream at the end of an urban block*. Jill Wrigley and Michael Sarbanes set out to make their yard a community resource in a low-income neighborhood with few green spaces. The woods and the stream are a natural attraction for people in the community, particularly children, and Jill and Michael opened up access to their yard to anyone who came down the street.

Intentional communities in Baltimore are reconceiving private space as community space as a way to foster nature, community, and related public goods in the city.

Over time, the space became a place where many children would spend time on a regular basis and that they would claim as a daily part of their lives. The yard became a shared space where neighborhood children, their parents, residents of the block, and Jill and Michael got to know each other. These relationships formed the basis for creating a culture and simple set of rules that govern how the space is used—treat each other with respect; pick up any trash you see; take care of the wildlife; when the streetlights come on, it’s time to go home. When I walked with Jill and Michael through their woods next to their home a few years back, we were followed by a curious child from the subsidized housing complex up the street. She was delighted to skip a rock across the stream wending its way through a space that technically was privately owned, but which she saw as a natural part of her daily life.

Jill and Michael were white-collar professionals and activists deeply committed to social justice and their church. They saw opening access to their “piece of nature” in West Baltimore as a way to build community and address social ills. In Sweden, public access can be viewed from multiple perspectives: as a shift from nature as something to be exploited to something beautiful and intimately linked to humans, as a site of environmental education where contact with nature supports human and community health, and as a means towards environmental justice and democracy [3]. Jill and Michael’s openly accessible property reflects all three of these perspectives, but especially their commitment to justice and democracy.

In Baltimore, justice and democracy mean not just the right to be present in nature, but the right to be influential. Reported low levels of public engagement among people of color in the U.S. result in part from limited access to factors that provide a gateway to engagement—factors such as white adults not thinking to ask adults of color to participate in a volunteer event, for example, and children attending schools where after-school and service learning opportunities are absent [4-6].

Jill and Michael don’t just provide the “right to be present”. This in itself is important—mothers from the subsidized housing project up the street have talked about how this slice of nature is a rare place where they get to think and relax. But Jill and Michael have also tried to address the importance of being influential. Children and families help to establish and enforce the simple guidelines for how to interact in the space. They participate in stewardship outings to clean and improve the land and stream. They engaged in the design and beautification process that converted a vacant, trash-strewn property on the same block into the Peace Park, a flexible community green space maintained by residents. Over the past several decades, Jill and Michael helped to establish a multi-faith, multi-racial, intentional community of families who have moved to the same block with a shared commitment to social and environmental justice, informally naming themselves the Collins Avenue Streamside Community. In these ways, the private common pool resource they own creates a public good that goes beyond access to nature to encompass the right of participation in fostering justice, building community, and more broadly, democracy.

At Collins Avenue Streamside, a privately-owned resource is not a private good. And solving the free-rider and tragedy of the commons problems associated with common pool resources does not rely on restricting access to private property. Yet solving these problems does assign individual rights and responsibilities to the resource—the right of access to nature, the responsibilities of respecting each other and the land, and the right and responsibility of participation in democratic processes in a neighborhood where those rights have been traditionally restricted.

But does Jill and Michael’s initiative counter the tenet that without government policies, undersupply of public goods will ensue? During the evolution of Collins Avenue Streamside Community, several government policies have supported the creation of the space. For example, city code enforcement tore down an abandoned house on the lot that became the Peace Park, and a regional effort to reline old sewer pipes significantly improved the quality of the water in the stream. But these efforts form a background, rather than a direct cause of the creation of the space. The space itself is largely a response to the very limited access to public green space in the neighborhood. So, in this context, the undersupply of public goods in the neighborhood set in motion private action to create those goods.

In Baltimore, families in the Collins Avenue Streamside Community don’t just support greening and social justice, they live greening and justice in their everyday lives. Jill and Michael have seen the rise of similar intentional communities in Baltimore, which are reconceiving private space as community space. They hope other private citizens will consider their streamside project and intentional community as a life choice to foster nature, community, and related public goods in the city.

* Jill Wrigley was a lawyer and university instructor who passed away prematurely in October 2016, leaving behind her husband, her three adopted children, and her Collins Avenue Streamside Community. We offer this short piece in commemoration of Jill’s extraordinary devotion and commitment in all facets of her life.

References

- Ostrom, E., et al., Revisiting the Commons: Local Lessons, Global Challenges. Science, 1999. 284(5412): p. 278-282.

- Harris, J.M., Environmental and natural resource economics: a contemporary approach. 2006, Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin. 503.

- Sandell, K. and J. Öhman, Educational potentials of encounters with nature: reflections from a Swedish outdoor perspective. Environmental Education Research, 2010. 16(1): p. 113-132.

- Flanagan, C. and P. Levine, Civic Engagement and the Transition to Adulthood. The Future of Children, 2010. 20(1): p. 159-179.

- Musick, M.A., J. Wilson, and J.W.B. Bynum, Race and Formal Volunteering: The Differential Effects of Class and Religion. Social Forces, 2000. 78(4): p. 1539-1570.

- Foster-Bey, J., Do Race, Ethnicity, Citizenship and Socio-economic Status Determine Civic-Engagement? 2008, CIRCLE: Boston, MA. p. 19.

Sheila Foster

Think of almost any city in post-industrial American in the 1980s—Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, New York. Failed urban renewal programs have left most of these places scattered with vacant lots, abandoned by their original owners and now owned by the city through tax foreclosures. Now consider that, in the midst of economically and socially fragile communities, neighborhood residents utilize these vacant lots to construct hundreds of community gardens. Residents sweep away trash and drug paraphernalia. They plant and cultivate trees, flowers, and vegetables. The gardens become places where residents of different ethnic backgrounds and ages interact, local food is produced, and crime is prevented (because the garden participants become the eyes and ears of the community). The gardens also provide the infrastructure for community interaction—sitting areas (benches and tables), playgrounds, water ponds and fountains, summerhouses—as well as for cultural and social events.

Questions of equity and distributional justice are key to the urban commons as a concept.

Fast forward to the 1990s. Urban revitalization is well under way; many suburbanites who left the city decades ago are now itching to return to the promise of safe, burgeoning city life. Private developers are interested in land once thought forgotten. City officials, too, are interested in previously abandoned lots, particularly in selling them to private developers for the construction of new housing and other developments. Towards this end, imagine that public officials in one of these cities announces plans to bulldoze hundreds of community gardens and sell off the lots to private developers. Officials argue that in the long run, the communities where the gardens sit would benefit from the new development and even promise to construct affordable housing on some of the sites. In response, neighborhood residents bring a lawsuit to stop the auctioning off of the gardens, but to no avail. They discover that they do not have legal claim or proprietary right to the lots. They are essentially short-term tenants of the city government with consent to use the land at the will of the city.

City officials characterize the lots as “vacant”, notwithstanding the community gardens operating on the land, and want simply to return the lots to their previous commercial or residential uses. The residents, on the other hand, contend that destroying the gardens would deprive their communities, especially the most vulnerable, of critical resources on which they depend. To highlight the resources provided by the gardens, and their loss should the gardens be taken away, residents engage in a rhetorical campaign to equate the gardens as akin to parks or “parkland”. Parkland receives revered protection under the “public trust doctrine”, an ancient legal principle adopted by American courts that preserves for public access and use certain kinds of natural, cultural, and urban resources and prevents them from being sold off or exploited for commercial profit or strictly private gain.

The idea that the community gardens are more than just a piece of undeveloped land, and more akin to a common pool resource, raises important questions for how we think about urban “nature” and the urban commons. In many ways, much of what we consider the urban commons shares characteristics of both a “common pool resource” and a “public good”. At first glance, nature in the city looks and sounds a lot like a common pool resource. Many natural commons, such as lakes and rivers, pre-existed many modern cities and are resources on which urban dwellers now depend for their water supply and other critical goods. However, there are equally as many (if not more) constructed “nature” commons in the city—such as manmade urban parks and lakes—which share more of the characteristics of many public goods. That is, they function much like other built infrastructure in the city; they accommodate multiple users without subtracting from their availability to others. In many instances, public parks and recreational rivers and lakes are even closer to other kinds of urban infrastructure—highways, mass transit systems, public swimming pools, schools, airports—than they are to the forests, underwater basins and irrigation systems that were the subject of Elinor Ostrom’s study of common pool resources.

Take Central Park in Manhattan, New York, which is an entirely manmade park whose construction was made possible only by the destruction of Seneca Village, which was settled by free black people and was a flourishing community of African Americans and Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century. The City government claimed the land using its eminent domain power and then evicted the residents, razed their homes, and built Central Park. A similar story unfolded in the mid-twentieth century, when the now infamous “Master Builder”, Robert Moses, whom Jane Jacobs famously took on, began a seven- year public works spree in New York. Over the course of this period, using public money, he built over a dozen bridges, over 400 miles of highways, over 600 playgrounds, and several iconic cultural buildings such as Lincoln Center and the United Nations. He often did so by using the power of eminent domain to evict working class and poor communities from these sites to accommodate these public goods.

Thus, much of what we might consider to be “urban nature” is some mix of a public good and a common pool resource. More importantly, the creation and destruction of these urban common resources are often contested and raise difficult choices about what kind of urban environment we want and value, and who benefits and pays the costs of these choices. What this means for the urban environment is that we need a version of the “urban commons” that accounts for these difficult choices. One often overlooked aspect of thinking about the urban commons, including constructed “nature” resources in cities, is the generative potential of shared urban resources. We should privilege and protect from destruction and over-development those urban resources, whether natural or constructed, that generate goods necessary for human flourishing in communities. In addition to being able to subtract or extract from shared urban resources, some of the most valuable resources in cities (both natural and constructed) are also a means to produce a variety of critical goods and services for its urban inhabitants.

The “commons” is thus an important conceptual framework for examining questions of resource access, stewardship, distribution, and governance. As with common pool resources—fisheries, forests, information, knowledge, and so on—the issue is often the scale of production and renewability of urban resources. Very few resources are infinite and, at some point, decisions must be made as to how and to whom to allocate urban resources and what kind of process that entails. The management and governance of urban commons should pay particular attention to, and account for, those less able to access and utilize urban assets to support human survival and flourishing. In this sense, questions of equity and distributional justice are also key to the urban commons as a concept, which can help to mediate the question of who should decide, and on what basis.

James Connolly

There are conceptual problems with viewing nature in the city solely as a public good or solely as a common pool resource, but common pool resource is closer to our current reality. In understanding why, we can also understand the political challenge of creating just and green cities.

The either/or options, “common pool” or “public good” will not take us where we need to go. More promising is the trend toward social-ecological coalitions.

First, we need to specify the full set of benefits that flow from the stock of nature in the city. Ecological benefits of urban green space include air and water filtration, temperature regulation, and habitat provision. Human health benefits are derived from the association between access to green space and reduced cardiovascular disease, reduced mental disorders, and improved child development. Meanwhile, there are measurable economic benefits, such as increased property values and increased tax revenues. Social benefits include greater connection to community for neighborhood residents and an expanded civic arena, which generates a more functional democracy.

This list of benefits could be much longer, which explains why inner city residents fight for equitable access to nature as a matter of justice. However, one thing that complicates this fight and the effort to conceptually categorize nature in the city is the fact that all of these benefits flow at once and affect one another. How do we decide which benefits to prioritize?

If we focus on certain ecological benefits of nature in the city, then the standard criteria for public goods are easily met. If urban natural areas are a public good, then, generally speaking, no one is excluded from accessing the flow of benefits and one person’s use does not diminish the capacity of another person to benefit. Ecological benefits, such as reduced toxins and cooler temperatures, can be accessed by all and are not diminished when the benefit is received. However, access to some ecological benefits (such as water drainage) and too many health, economic, and social benefits are often curtailed by institutions that limit who can occupy certain areas of the city. Thus, those advocating for urban greening as a public good emphasize the universal ecological benefits.

If we focus on the economic benefits of urban natural areas, then the standard criteria for a common pool resource are likewise easily met. If the stock of nature in the city is a common pool resource, then (generally speaking) anyone can access the flow of benefits, but—differently than a public good—these benefits are finite, and one person’s use limits availability for others. In this circumstance, people are rivals, competing for a resource and struggling to negotiate governance arrangements that ensure it remains available across space and over time. When urban green space demarcates high-end neighborhoods, as is the case with New York’s High Line Park, Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway, and Austin’s west side preservation efforts, then the economic benefits are mostly captured by a few. Soon, other benefits of urban natural areas are also increasingly spatially segregated according to the logic of gentrification. Under these circumstances, certain people access the benefits of urban nature at the expense of others meaning green space is no longer defensible as a public good and instead needs to be viewed as a common pool resource with associated governance challenges.

Of course, some ecological benefits remain accessible to all residents despite gentrification processes. Thus, categorizing urban greening as a common pool resource is also a contestable proposition. While it is a tautology, it is necessary to remind ourselves that these theoretical models only partially accommodate messy reality.

In sum, if you focus on ecological flows, then nature in the city is a public good; if you focus on economic flows, then urban natural areas are a common pool resource. I suggest that this conflict means we should see the stock of urban natural areas as existing along a spatially and historically contingent spectrum between common pool resources and public goods. In 1970s America, post-industrial abandonment made nature in the city more of a public good. Now, with urban space treated as a luxury item, greening is experiencing steep privatization pressures and is closer to a common pool resource. The broad urban context matters and those seeking to green the city should adjust with the context.

What does this tell us about the political challenge of creating just and green cities?

Relying only on the public good argument delegitimates those who focus on the non-ecological benefits of greening. Meanwhile, ignoring the public good aspects of urban greening weakens the political position of those advocating for just and green cities. As environmental justice advocates have long understood, such either/or positions will not take us where we want to go. Rather, a more promising trend is toward the formation of social-ecological coalitions, perhaps focused on human health and civic engagement. Precisely because these benefits are hard to put in any one conceptual category, they provide fertile political ground.

Phil Ginsburg

At its best, nature in an urban environment is a public good whose enjoyment by one neighbor does not impinge on the enjoyment of nature by another, but instead enhances it by providing a place for people to connect face-to-face and to take full advantage of the benefits of being outdoors.

Maintaining a constant feedback loop with park users can allow us to create well-loved public spaces and a social contract we can all adhere to.

San Francisco is blessed with 224 parks, occupying roughly 15 percent of the real estate in the city. One thousand acres of that land is pure nature: miles of hiking and walking trails, breathtaking vistas and rich habitat. Every day, I see heartening examples of coexistence and the sharing of space that enriches lives and our public space.

We are not, however, immune to the challenges of managing open space in a dense urban area, which can include user conflicts, trash and vandalism, and disagreements about when and how and why to renovate a park.

We are not arguing the importance of open space versus development. There is a high level of agreement in our city about many things; there is broad consensus that open space makes the city more livable, and we have an active and engaged citizenry that believes in fighting global warming, expanding recycling and composting efforts, and reducing the carbon footprint of our parks.

On our best days, the combination of good planning and design, positive activation, engaged stewards, education, and enforcement keeps our parks as places that we can enjoy without interfering with our neighbors. If one of those pillars falls, however, conflict arises and parks can shift from a public good to a tragedy of the commons, where our shared spaces are riddled with congestion, overuse, and inconsiderate behavior.

Ideally and in practice, we all decide how public space will function—government makes choices in partnership with its citizens, informed by the best thinking and innovative ideas we can find.

An essential component of our strategy has been to place a high priority on community outreach, volunteerism, and engagement, and to maintain a constant feedback loop with our diverse park users, who share with us their priorities and how we can better facilitate connecting them to nature.

A prime example of this model in action is the recent renovation of Kezar Triangle, a 2.8-acre spot of parkland on the outskirts of Golden Gate Park, adjacent to one of our more popular stadium sites. In years past, the triangle was little more than a pedestrian throughway for commuters and an unfettered area for dog owners to exercise their furry friends. A community effort to organize, fundraise, plan, and design a repurposed park space in partnership with our department has resulted in a lively, activated multiuse park with an eager volunteer stewardship base.

Sure, government is the ultimate decision-maker on staffing levels, infrastructure, amenities, policy, and enforcement priorities, and our neighbors are the ultimate decision-makers on how they interact with their public spaces. But when we align and work together to create well-loved public spaces and a social contract we can all adhere to, everyone wins.

Jeff Hou

Reconstructing City Nature as Commons

Nature spaces in the city—as with air, light, and water—can indeed be conceived as a public good or common pool resource whose management is to be determined by its citizens. In reality, however, things are obviously far more complicated. The rise of property ownership over the course of centuries has impinged on many preexisting practices of common resource management in traditional societies. In contemporary cities, the prevalent, neoliberal form of urban governance has further blurred the line between public good and private interests, and muddled the process of collective decision-making. “Nature spaces” in cities are increasingly far from a public good, and are, instead, commodities for those who can afford them.

The development and maintenance of public parks and open spaces in which much of urban nature exists are funded increasingly through myriad private and public funding sources with diffuse decision-making processes and accountability. While the public does benefit through many philanthropic and even private efforts, they are not necessarily engaged in decision-making that influences the outcome of those projects and how they are programmed and maintained. In growing cities, development and improvement of parks and open spaces are inextricably tied to processes of gentrification and displacement of individuals and communities. These “nature spaces” tend to serve only those who are able to live close to them. As such, “nature” is increasingly far from a public good, and is instead a commodity for those who can afford it.

How can we overcome this conundrum? How can citizens and urban multitudes reclaim and reconstruct the “nature” commons within the current framework of urban governance? There are a few things in Seattle, my current home city, that can serve as a starting point for discussion. First, at the institutional level, the City of Seattle faces significant fiscal constraints, like most other North American cities. But unlike the public-private partnership model used to develop major public parks in other large cities, Seattle citizens went to the ballot to pass tax levies that provided hundreds of millions of public dollars for development of new parks and the refurbishment of existing ones in all corners of the city. The use of such money was overseen by a Citizen Oversight Committee. The result is a network of urban open spaces that are accessible to and enjoyed by communities of different economic circumstances.

At the community level, citizen engagement is key to develop agency, participation, and attachment in the active stewardship of nature spaces in the city. The P-Patch Community Gardening Program under the City’s Department of Neighborhoods provides one such opportunity. Through community gardening initiatives and advocacy, citizens, neighbors, and civic organization form networks that extend beyond those focusing on gardening to include efforts in promoting green infrastructure, urban agriculture, and environmental education.

Public space activism is another important vehicle for civic engagement and as a form of resistance against forces of private interests and neoliberal enclosure. As early as 1971, citizens in Stockholm gathered and succeeded in protecting a beloved grove of elm trees at the King’s Garden (Kungsträdgården) from being taken down to make way for a subway station. More recently, residents in Istanbul staged protests to protect Gezi Park against a proposed development on the site. Though the protests were violently suppressed by the authorities, they inspired broad-based organizing and discussion concerning issues of the environment, authoritarian control of the state, and rights to the city. The cases in Stockholm and Istanbul are two examples of many instances around the world in which activism and social actions have been instrumental in protecting nature spaces (whether they succeed or not) and in engaging discussion and debate concerning the role of nature in the city. It is through these actions and mobilization that nature as a public good can become a subject of public debates and advocacy—a social and political process through which urban nature as a public good can be articulated and clarified in our changing society. I argue that it is through processes like this that the meanings and significance of nature in the city can be not only reclaimed, but also reconstructed.

Mary Mattingly

Swale: An Experiment in a Commons

The role of trust

A floating food forest, Swale is an experiment in a commons in New York City. With roughly one hundred acres of community garden space compared to 30,000 acres of public parkland, picking food on New York’s public land has been illegal for almost a century.

Not only do we need more people at the table, we also need more opportunities for people to build the table.

In a city where liability often trumps trust (even when benefits outweigh the harms), New York City Department of Parks & Recreation’s §1-04 Prohibited Uses initially stemmed from the concern that a glut of foragers would destroy an ecosystem.

Swale is an edible landscape built on a hopper barge that utilizes marine common law in order to circumvent local public land laws. In this way, Swale is able to dock adjacent to public land and allow people to pick edible and medicinal perennial plants grown onboard for free.

Collaborative building

Building together is a process of physical, mental, and social transformation. Because we all have much to teach each other, Swale has been improved by insights from visitors, and also by learning more about the Parks Department’s current concerns over public access to edible plants. These include differing degrees of plant knowledge, alternative maintenance needs for edible landscaping, and a philosophy of conservation on parkland.

The alliances that steward Swale are small examples that stress the large importance of urging more people to be involved in caring for our common home, and therefore in stewarding water and lands so that they may continue to be safe spaces to utilize in multiple ways. One year after the launch of Swale, the Parks Department will pilot the first public “foodway” at Concrete Plant Park in the Bronx. This signifies a change and a realization that basic human needs for access to healthy food outweigh perceived liabilities. Not only do we need more people at the table, we also need more opportunities for people to build the table.

Social love as a commons

Urban food forests won’t feed a city like New York anytime soon. However, a multitude of different approaches that are closer to home are necessary if we are going to address the role of industrial farming in climate change, and also begin to heal from damage done to the environment, ourselves, and our neighbors through industrial forms of production that neglect human and environmental health.

As a country, the United States has sped towards privatization of everything. So it is no wonder that movements towards food sovereignty and rebuilding common spaces continue to grow stronger. The ability to bridge understandings, communities, and knowledge sets with social love and dignity are urgently needed in order to understand (and then part ways) with systemic social and environmental violence. Social love is itself a commons, and it is what moves us to devise larger strategies together to halt environmental degradation and to encourage care. It’s difficult to presume we can begin healing nature and the environment without, at the same time, being able to trust in our fundamental human relationships.

Oona Morrow

Cities pose numerous challenges and opportunities for commons. As Amanda Huron observes, the sociospatial conditions of cities such as density, overlapping uses, cultural diversity, the coming together of strangers, and high levels of capital investment can make cities particularly challenging for creating commons in their traditional forms—that is, place-based communities taking care of the territorially bound resources they depend on.

Urban socio-natures are both common pool resources and public goods—recognizing this is a necessary first step in establishing the ground for the city as commons.

Yet, urban spaces have also proven to be fertile ground for unbounding the commons and moving beyond the logics of scarcity and economic rationality that are embedded in Hardin’s tragedy of the commons. In cities, we discover commons that are abundant and unbound, overlapping in time and space, cultural and digital, material and immaterial, public and private, generative, and in dynamic states of becoming.

I’d like to begin by reflecting on why public goods and common pool resources are placed at odds with one another in this question. Public goods such as parks, fresh air, health care, and infrastructure signify commons in their most open and inclusive form. They are open access, and they exist for the benefit of all urban inhabitants. Depending on their social and material qualities, they may also exhibit the common pool resource characteristics such as sub-tractability and difficulty of exclusion. However, these public goods are rarely recognized as commons—it is often not until they are threatened through privatization or enclosure that they are recognized as such. Sometimes these public goods don’t feel like commons at all. Their rules, regulations, and governance processes might feel exclusionary or too top-down. Rather than encountering urban infrastructures, natures, and spaces as commoners who have the capacity to alter, repair, steward, or care for these resources, we often encounter them as consumers of services provided by an (often underfunded and overburdened) administrative state. I argue that urban socio-natures are both common pool resources and public goods, and that recognizing them as such is a necessary first step in establishing the ground for the city as commons. This “both/and” conceptualization allows us to recognize the place based claims of local communities on the socio-natures they care for and benefit from, while also suggesting that such commons based governance strategies can usefully operate at larger administrative scales, and may at times need to “go public” in order to ensure the equitable distribution of environmental benefits.

What does this “both/and” conceptualization of urban socio-natures as common pool resources and public goods look like in practice?

My research on the diverse economies and nature-society relations of food provisioning in cities has led me to explore commons in Boston and, more recently, in Berlin. In greater Boston, I got to know many people who were experimenting with collective forms of food provisioning. They were reclaiming vacant lots for community gardens and urban farms; foraging for edible plants in parks and on the verges of sidewalks and private yards; and harvesting, sharing, and caring for backyard fruit trees. Their practices produced common pool resources—gardens, urban orchards, knowledge of edible plants. But, they also sought to steward these resources as public goods; requested that city arborists and the parks department plant more edible plants; advocated for zoning changes that would make it easier for people to grow food on vacant lands and share or sell that food; and showed up to resist when the public parks they used for foraging were threatened by development.

In Berlin, I got to know people who treated public goods as if they were always already common pool resources. The mapping platform mundraub allows members to share their local foraging knowledge, enabling a potentially infinite pool of harvesters to reclaim the edible trees and plants growing on public property as commons. The borough of Pankow has gone a step further to pass legislation for the concept of Edible Borough, which provides locals and mundraubers permission to plant, care for, and harvest from fruit trees in designated public parks. All over the city, Berliners have been reclaiming land for commoning through a vibrant and thriving community gardening movement. The landmark 100% Tempelhofer Feld referendum over the future of an abandoned airport in Neu Kölln demonstrated that not only do Berliners want public goods, such as parks and green spaces, they want those goods to be open for commoning—for community gardening, for wilderness and wildlife, for leisure and art. The capacity to create common pool resources out of public and private goods in Berlin is truly inspiring, and all the more necessary during a time when so many public goods—from vacant lots to social housing—continue to be privatized and sold off to pay interest on municipal debts. For public goods to remain public in Berlin and beyond, they need to be recognized as commons, and to be used, governed, and cared for as common pool resources.

Harini Nagendra

Nature in the city is a confusing, contested category. Some would like it to be a public good: an iconic park, large lake, or wetland that exists to serve the needs of the city and all its people, cleaning up its polluted air and recharging its water. Others consider nature to be a common pool resource, co-created with the local community that interacts with the resource by planting, restoring and harvesting, via fundamental acts of commoning that increase the binding between otherwise disparate and disconnected city dwellers. Some others prefer to sequester nature in the form of a club good, shared by a few (a members-only “club”) in an apartment complex or gated community, or a private good reserved exclusively for their homes: this is something one can see real estate developers capitalizing on as they offer ultra-rich luxury homes, advertised with private butterfly gardens and lakes in cities such as Bangalore.

Cities in many parts of the world are experiencing an alarming shift in the framing of nature in the city away from a commons, repositioning it exclusively as a public good.

An urban ecosystem can constitute a public, a commons, and a private good at the same time. Thus, the Kaikondrahalli lake in Bangalore constitutes a public good, because it increases ground water percolation, which is then pumped out and used to supply the city with water. It is a commons, for the fisher folk and grazers who use the lake for its abundant supply of fish and grass. It is also a private good, for those who own apartments with balconies with a view overlooking the lake, in which they sit with their morning cups of tea to enjoy a rare moment of urban peace, and de-stress in harmony with nature. The lake can, it seems, be all things to all people.

Why, then, should we care about this definition? The distinction between public, private, and common goods is not an esoteric categorization dreamt up by political scientists with no bearing on reality. It is clear from many previous discussions at The Nature of Cities, that the increasing privatization of nature is something we all ought to be worried about. However, cities in many parts of the world are also experiencing a silent, but widespread shift in the framing of nature in the city away from a commons, repositioning nature exlusively as a public good. This is alarming, as well.

In Bangalore, my colleagues Seema Mundoli, B. Manjunatha, and I recently looked at what happed to the commons in 18 peri-urban villages that are now engulfed by the city. Government records indicate that these villages had as many as 43 urban woodlots—locally called “gundathopes”—just a few decades ago. An average-sized grove typically contained upwards of 20 trees, majestic collections of jackfruit, mango, tamarind, banyan, and fig that provided shade and fodder, food, timber, and shelter. Many also contained sacred elements such as stones and anthills, and were worshipped as sacred groves, in addition to being used as commons.

Of these 43 groves, 20 are now gone—erased so effectively from the landscape that in many villages, people did not remember the physical locations where the groves once existed. Of the remaining 23, many had no trees left, and were in a pitiable condition of disrepair. What has replaced these groves? We expected that they would have been cannibalized by wealthy private interests and converted into large private homes or business. Instead, we found them converted to “public use”—sites of government offices, schools, and community centers; allotted to low-income housing schemes; or razed to make way for roads, markets, and community temples.

Why was this decimation of groves so widespread? Because the village lost control over its commons. For generations, the local village maintained its groves as common property regimes. Decisions to plant, extract, or fell were collectively taken by local residents. As the city expanded to engulf villages, their groves became properties of the city at large—they went from commons to public goods. In a city cramped for space, it is easy to see why administrators sitting in distant offices prioritise the need for a school or community center over a bunch of trees. It is only the local residents, after all, who valued these as much more than a bunch of trees. As a commons that was central to their identity, culture, and placemaking—a value they have now largely lost, and which only the elderly seem to be able to recall. Ironically, in rare instances where groves have been protected, the local village has actively made efforts to convert them into landscaped parks for recreation, trying to retain control over their grove instead of “losing” it to the city.

The reframing of urban commons as public goods is widespread in Indian cities. A recent article on the cleanup of Bangalore’s largest lake, Bellandur (so polluted that the foam on the lake regularly catches fire, bringing international news coverage with it) highlights that the cleanup will restore the lake as a public space, but will destroy the livelihoods of hundreds of commoners—fishers and grazers—who depend on the lake. It is interesting that it is a business paper that carries this analysis, which provides a good example of inclusive business coverage. The discussion, which carries quotes from a number of experts with influence, clearly shows us that when urban nature is reconceptualised as a public good, the rights and requirements of the local community as stewards and commoners are given short shrift.

The trajectory of de-commonisation of urban nature is not inevitable. There are hundreds of examples around the world where commoners work to restore and maintain pockets of urban nature which also service the city and its public. But to argue for the co-construction of nature in the city as a commons and a public good, we need to make a strong case for keeping the distinction alive. And explain why it matters.

Phil Silva

“Garden is a verb and a noun,” my friend John used to say.

In the late 2000s, John and I were just two of more than a hundred members of the Prospect Heights Community Farm, a 3,500-square-foot garden slotted between an old four-story tenement and a stately brownstone in the heart of Brooklyn, NY.

Urban gardens demonstrate the qualities of common pool resources, public goods, and private lands—these aren’t truly categories in the restrictive sense, but interchangeable interpretive lenses.

The “farm” provides a sliver of verdant open space in a densely-populated and rapidly redeveloping neighborhood. Yet a tall steel fence limits public access to the site. Gardeners come and go as they please, though, swapping a few hours of volunteer time and a couple of bucks in annual dues to get a little brass key to the rusting padlock on the garden gate.

Most gardeners volunteer by keeping “open hours” on weekends and weekday evenings, throwing open the gate to welcome curious visitors. Others help with weeding and pruning, raking and watering, making occasional repairs to the shed or the compost bins or the rainwater cisterns. The constant work of maintaining the farm means that things are always changing. Trees damaged in windstorms are cut down and replaced with vegetable beds. Overgrown shrubs are pruned to create new habitat for pollinating birds and insects. Fences are painted and paths are rerouted and crops are transplanted.

Every chore is the result of a choice: to prune (or not), to plant (or not), to paint (or not). Individual gardeners make millions of little unilateral decisions as they go about their weekly work. Most decisions go unnoticed, while some become the source of contentious and prolonged debate at monthly meetings. One group of gardeners can’t bear to see anything change. Others are excited by opportunities to tinker with our little patch of the urban landscape. When these two worldviews inevitably clashed, John would calmly remind us of the grammatical dexterity of the very word that brought us all together: garden is a verb and a noun.

I’m not precisely sure if a site like Prospect Heights Community farm is a public good or a common pool resource. The two concepts often overlap, as James Quilligan points out. Maybe it’s both. Looking at the farm through the lens of public goods, we see a resource that is repeatedly renewed through active and intensive use—if you think of the act of gardening and all its associated tasks as a kind of “use”. And you can be sure there are freeloaders—gardeners that do the bare minimum to enjoy the space while others take on all the hard work. Then again, the site is just four-fifths of an acre and cannot grow beyond its property boundaries. Only so much of the space can be actively gardened by its members before things start to get tragic in the commons.

Maybe the farm is neither a common pool resource nor a public good. Access to the garden is excludable to the general public, after all. And unlike municipally-owned parkland, the deed to the farm is held by a private land trust chartered as a non-profit organization in New York State.

So, what’s my point? Just as garden is both a noun and a verb, it may be that gardening sites, such as Prospect Heights Community Farm, can, in practice, demonstrate the qualities of common pool resources, public goods, or private lands—depending on what one chooses to emphasize. These categories aren’t truly categories in the restrictive sense, but interchangeable interpretive lenses that shape the way we see, interpret, and understand any plot of land and its relationship to particular people.

Maria Tengö

How can cities secure the sustainability of urban green spaces and their ecosystem services while, at the same time, accommodating a wide range of demands and pressures?

The ultimate responsibility for governance of urban green and blue infrastructure must lie with city authorities, but there is great opportunity for partnership with civil society.

I argue that a portfolio of approaches are needed, a portfolio that can build on and nurture people’s engagement in and care of particular places and activities, while also recognizing the need for citywide (and beyond) coordination of initiatives to sustain the sustainability of urban green spaces and its ecosystem services.

As found in numerous examples in The Nature of Cities, from the northern as well as the southern hemispheres, that engagement with civic organizations and local citizens can restore and protect urban green spaces. Such engagement can lead to a number of positive benefits: it generates opportunities for recreation and nature-related experiences in the city; contributes to well-being through meaningful community engagement; and builds capacity for civic engagement and local democracy, as is shown, for example, around community gardens in Berlin. Co-management of parks, wetlands, or similar site types can be a useful way to formalize civic engagement in green space management, and to connect the agency of actors who are strongly engaged and who care for the values generated in parks and other public spaces with the resources and technical know-how of formal authorities.

However, to secure the range of ecosystem services generated by urban green and blue spaces, paying attention to civic engagement and social aspects is not sufficient. Urban ecosystems are often fragmented and isolated, and their biodiversity and ecology are dependent on connectivity between areas within the city as well as with ecosystems outside the city. The connectivity matters for flow of water and movements of animals and seeds, for example. Different ecosystems in the city can offer complementary resources for bird or small mammals. Matching scales of governance with the scales of critical ecological processes is a key challenge for environmental governance in cities. Thus, preserving biodiversity and ecosystem services requires targeting and managing flows and interactions at a larger landscape scale, beyond the internal qualities of individual spaces that can successfully be stewarded by civic groups.

Furthermore, some areas may be critical as urban green infrastructure, but lack characteristics that appeal to and engage citizens in their protection or restoration. Continued stretches of street trees that improve air quality, or green stretches around highways that are critical for water infiltration, are not very likely to be cared for by local citizens (even if individual trees may be protected). In the words of a Stockholm manager: “I focus my energy on the green spaces that nobody cares about”. Citywide formal authorities are required to coordinate initiatives, to secure governance of large-scale ecological processes, and also to maintain a technical knowledge base unlikely to reside in volunteer organizations.

For these reasons, I argue that the ultimate responsibility for governance of green and blue infrastructure in the city must lie with city authorities, but there is great opportunity for partnership and network approaches that can open up space for civic groups to manage and to have a strong influence over form and function of particular areas. As such, awareness of and the ability to identify urban environmental stewardship is required among city managers. Local initiatives can take many different forms that may not fit immediately within conventional arrangements, and creating opportunities for stewardship initiatives to emerge and develop can be a key role for authorities. Experimentation and a portfolio of approaches can include direct management, as well as different forms of partnership with varying degrees of citizen engagement.

See also: Andersson, E., J. Enqvist and M. Tengö. 2017. Stewardship in urban landscapes. In: The Science and Practice of Landscape Stewardship, Bieling and Plieninger (eds.). Cambridge University Press.

Raul Pacheco-Vega

I have a somewhat problematic notion with the idea of the “right to the city” and that of the “urban commons” when it comes down to who gets to do what, where, and when—the traditional questions that public policy analysis theories ask. As an anecdote, I walk through the streets of Aguascalientes, the city where I live, and I witness several small, yet painful-to-watch actions that some residents take. These happen on a regular basis. For example, a few weeks ago, I was walking on the street, and saw a driver drop the cellophane that covered the candy he was about to consume. I have also witnessed parents who not only enable but encourage their kids to throw garbage on the floor. This lack of basic respect for the rule of law, these small-yet-visible infractions, drive me bonkers. It’s almost as though these citizens were disrespectful because they didn’t feel like owners of the city. Or maybe they feel like The Owners? Who has a right to access public services? Who should be responsible for taking care of their urban environment? And when will individuals take responsibility for their actions, particularly when these have a negative impact on their shared environment?

There is a right to the city, but it should be accompanied by a duty to the city.

I am always concerned when thinking about shared access to a valuable resource, particularly when these include urban amenities such as lakes, parks, urban forests, and so forth. As someone trained in the Elinor Ostrom school of thinking, I am hopeful about self-organization to protect shared resources, but I’m also skeptical at times. That’s how I can let my personal and academic selves coexist: by believing in individuals’ ability to find ways to access resources but not deplete them, but also keeping a watchful eye on their behaviour and ensuring that they follow governance rules that we all have previously agreed on.

I think part of the discussion on the urban commons that gets overlooked and glossed over is the issue of WHO is responsible for the shared resources. Not only for their governance, but also for their conservation. Sharing urban commons is an activity whose implications go well beyond the RIGHT to access public spaces. While there is some value to the “right to the city” approach (particularly the “No One Is Illegal” model), whereby individuals have a right to be within a specific space, just by virtue of actually being physically there, it’s more complicated than that. The cityzenship approach espoused by Vrasti and Dayal is intriguing, because it argues that:

“citizenship […] is the right to the city, the urban commons, extended to all residents, regardless of origin, identity or legality, based on the principle of ‘rightful presence’ […] The urban commons include public infrastructures as well as public spaces, places of culture and education, cafes, the street and the street corner along with the capacity to make and unmake these spaces” (Vrasti and Dayal 2016, p. 994).

As lovely as the sentiment depicted by Vrasti and Dayal is, the question remains: WHO is responsible for maintaining those urban commons? Who shares in the responsibility (and therefore in the costs)? And when can access to the urban commons be denied or limited? Under what circumstances can we afford to limit the accessibility of shared urban spaces? Approaches such as cityzenship gloss over the need for public service delivery and the role and responsibility of local governments in providing those services. Moreover, it’s important to remember that these public services have costs that need to be borne out by municipal agencies. Such city-level organizations provide services, including cleaning up, watering gardens, treating wastewater from toilets and other locations, and collecting and disposing of refuse. Therefore, one can’t simply let individuals access urban commons without some sense of shared duty and responsibility towards those resources.

While it is clear that urban commons (and, in particular, “urban green commons”, as defined by Colding and Bartel) are useful resources for communities intent on building resilience and enhancing cultural, ecological, and biological diversity (Colding and Barthel 2013), we also ought to build specific norms that delineate who is responsible for what and when. This is where policy theory thinking can help us out. To manage urban commons, we need a diversity of policy tools and mechanisms to guarantee access, but also conservation and preservation. This is also an area where common pool resource theory (or commons theory), as espoused by Professor Elinor Ostrom, can help us build new strategies for urban commons’ governance. In particular, as Colding and Barthel indicate, institutional diversity (Ostrom 2005) can help create new models of governing the urban commons because citizens and service providers aren’t locked into one particular model of public service delivery and regulation.

“[B]roader participation in urban green commons is more likely to succeed when a diversity of institutional options exists for their arrangement in a city. Such diversity provides a better matching of different individuals’ preferences and motives for participating in collective green-area management. Hence, policy makers and planners should stimulate the self-emergence of different types of UGC […]” (Colding and Barthel 2013, p. 163)

Parks are particularly important urban commons that need to be properly managed and governed because they enable everyday participation, as well as building social capital, creating network ties, and enhancing cultural and social diversity. Moreover, “parks are a mark that somebody cares about the neighbourhood; they make a nice place” (Gilmore 2017, p. 39). Nevertheless, parks need to be cared for, tended to, and maintained. Therefore, it’s important to place a system of urban commons governance that assigns roles, duties, and cost-sharing to all members of the urban ecosystem within which the commons exists. At the same time, it will be important to enable members of this urban ecosystem to have free, if governed, access, and to enforce rules and norms aimed at sustaining the urban commons.

In closing, I do believe that there is a right to the city, but it should be accompanied by a duty to the city, as well. This is an area where coproduction thinking can be helpful. Coproduction is defined by the sharing of responsibilities in offering a public service. Citizens and governments both participate in the provision of this service (Ostrom 1996). But the answer to the question of “how can citizens and governments coproduce their public services” will be the topic of another TNOC discussion.

References

Colding, Johan and Stephan Barthel. 2013. “The Potential of ‘Urban Green Commons’ in the Resilience Building of Cities.” Ecological Economics 86:156–66. Retrieved (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.10.016).

Gilmore, Abigail. 2017. “The Park and the Commons: Vernacular Spaces for Everyday Participation and Cultural Value.” Cultural Trends 26(1):34–46. Retrieved (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09548963.2017.1274358).

Ostrom, Elinor. 1996. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development 24(6):1073–87.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, New Jersey and Oxford, UK: Princeton University Press.

Vrasti, Wanda and Smaran Dayal. 2016. “Cityzenship: Rightful Presence and the Urban Commons.” Citizenship Studies 20(8):994–1011. Retrieved (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13621025.2016.1229196).

Diana Wiesner

Iniquity for all1: The Right to the Poetics of Nature and the Duty to Care for It

After deciding to risk answering the roundtable discussion topic from my realm of ignorance and intuition, a multitude of other questions immediately came to mind: What does the word “nature” signify in city dwellers´ collective imagination? Cities can regulate resources without depleting them. But in many cities, Nature is reduced, contaminated, and its availability diminished. Nature poetry should be equitable for all.

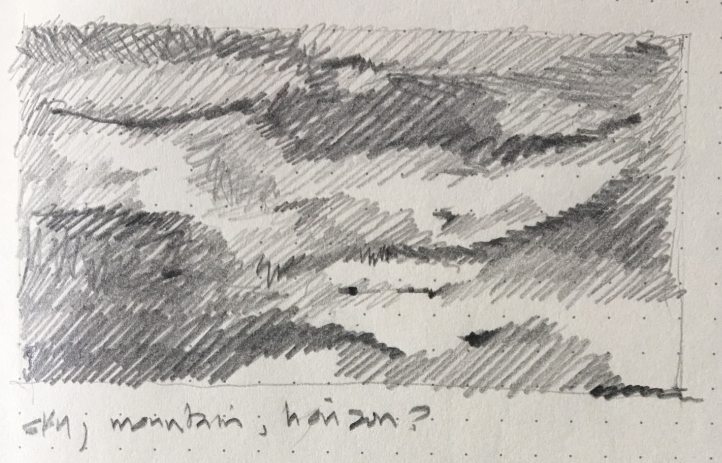

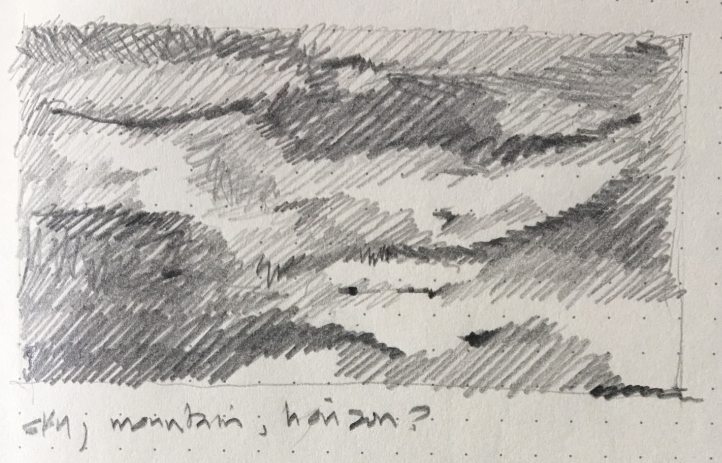

Here, I intend the term “collective imagination” to refer to the desires or interpretations held by the majority of people; in this case, I’m talking about “the common man or woman’s point-of-view” on “green” in the cityscape—that is, protected natural areas, urban tree planting, waterways, and other natural features, such as mountains and woodlands. However, the cityscape contains an infinite number of life forms in which nature is held manifest: dazzling sunlight, the ever-changing hues of the sky’s color, atmospheric moisture, the way the wind blows, the sound of rainfall and the land´s slope toward the horizon.

In addition, there are two matters that must be kept in mind when discussing public property: the idea of property itself, and citizens’ duties with respect to its care and conservation. In the case of Colombian cities, the debate is focused on whether the state should be the owner and administrator of natural and protected areas to ensure public access and, thereby, to eventually serve the majority’s need for recreation and services. On the other hand, there are those who maintain that these areas should be kept in private hands, but made available for public use under a public/private administrative plan to guarantee sustainability. A third view makes the case for the public’s inherent right to enjoy nature, with the corresponding duty to respond for services rendered. This is linked to the manifestation of life where nature makes itself seen and heard and felt in the city: it is part of urban poetry. It is the poetry of nature that provokes feelings that in turn produce a specific landscape, one brought about either by nature’s deficiencies and austerity, or by its abundance.

Are these manifestations inequitable for all? Life-giving expressions that give rise to individual narratives cannot be considered property. Interpreting nature in the city is an infinite process carried out by the multitude of observers who are roaming and experimenting in the urban landscape. Individuals encounter spirituality on their own terms: by breathing the air; by seeking well-being, comfort, an aesthetic pleasure; by living through earth tremors, or dry, hot days, or wet and rainy ones. Nature in the city should not be seen as a resource merely to be exploited.

Can a renewable commercial forest be compatible with urban needs? In recent years, the idea of fostering rural enterprises within the city has become more acceptable. A number of agricultural activities could be included to round out the idea of “rurality” in the city; these would focus on introducing rural occupations and the rural aesthetic into the metropolis, thereby enhancing urban poetics by impregnating neighborhoods with greater meaning and symbolism.

Biodiversity is the source of ecosystemic services, and the state must take on the responsibility for their equitable administration and regulation. Public goods belong to the community, and they cannot be consumed by having their availability limited to others. The so-called common pool resources concept does just that: reduces availability to others. But, there are ways in which the community can regulate these resources without depleting them. However, in many cities, what happens is that they are reduced, contaminated, and their availability is diminished.

In consonance with the voices of indigenous peoples, Nature belongs to itself and has a duty to itself and possesses its own right to exist. Such has been the case of the Whanganui River in New Zealand or of the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers in India, where the rights of water sources were recognized as being vitally important to their respective countries. That is to say, these rivers were granted the same legal rights as any individual before the law. Similarly, the indigenous communities in Ecuador claim that, “Nature, or Pacha Mama, possesses the right to be respected in Her existential integrity and that Her vital cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes must be maintained and regenerated”.

The response to all of these questions may be summed up in the profound answer given by an indigenous mamo from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia: “No, I have no rights, but the river has rights, the wind has rights, the mountains have rights. All we have is the duty to protect them2″.

Notes:

- Title inspired by the 2003 documentary film directed by Jacob Kornbluth

- El Espectador. The Nature Conservancy. María Paula Rubiano¿Rights for rivers? Not such a crazy idea.

Translated into English by Steven William Bayless, April, 2017

Inequidad para todos[1]: derecho a la poética de la naturaleza, deber de mantenerla.

Aparentemente la pregunta “Is nature in the city a common pool resource, or a public good?” puede iniciar una interesante discusión entre economistas, sin embargo, he decidido arriesgarme a contestarla desde mi ignorancia e intuición. Inmediatamente, surgen muchas mas preguntas, ¿cual es el imaginario del significado “Naturaleza” en la ciudad”? Imaginario, entendido como el deseo o interpretación de muchos, podría deducirse que esta asociado por el ciudadano de a pie, a la presencia del verde en la ciudad. Áreas protegidas, arborización urbana, rondas hídricas y componentes naturales como montañas, bosques entre otros. Sin embargo, el paisaje urbano, presenta infinitas formas de vida que son el manifiesto de la naturaleza: el brillo solar, el color del cielo, la humedad, el viento, el sonido de la lluvia, el suelo que se inclina en el horizonte.

Adicionalmente, hay dos temas a entender respecto a los bienes públicos: el concepto de propiedad, y los derechos y deberes de los ciudadanos sobre la misma. Respecto al primero, en el caso de las ciudades colombianas, la discusión se centra en si estado debe tener la propiedad y la administración de las áreas protegidas y naturales para que permitan el acceso público a la mayoría o bien su disfrute y servicios. Hay posiciones respecto a la posibilidad de que pueden ser privados pero con uso publico y administración mixta para garantizar su sostenibilidad. Por otra parte, se habla del derecho al disfrute de la naturaleza como bien común y un deber ciudadano de corresponder a sus servicios.

Los manifiestos de vida y de presencia de naturaleza en la ciudad, reflejan una poética. La poética de la naturaleza expresada en sentimientos que puede producir un determinado paisaje, por carencia y austeridad o por abundancia. ¿Son estos manifiestos inequitativos para todos?. Las expresiones de vida que despiertan emociones o narrativas en los individuos, no pueden tener propiedad. La interpretación de la naturaleza en la ciudad es infinita, por la cantidad de observadores que recorren y la experimentan. El individuo la aprovecha espiritualmente, la consume en aire, bienestar, confort, estética, pero también sufre la inundación, el sismo, el exceso de calor o de humedad.